Musicians pioneered desegregation at East Carolina College, from the 1958 Dave Brubeck Quartet concert to the Cavaliers and beyond to Count Basie and a host of others, with line-crossing performances that delighted the student body. African-American undergraduates were admitted, beginning with Laura Marie Leary, though very slowly and selectively. By the mid-1960s, a number of other colleges and universities that had desegregated years before East Carolina proceeded to include African-American students in their intercollegiate sports teams. An athletically ambitious school, especially as led by President Leo W. Jenkins, East Carolina followed the lead of other schools with the desegregation of athletics from 1966 forward.

Indicative of the revolutionary nature of this aspect of desegregation was the fact that in the mid-1950s, well before East Carolina’s desegregation, a question had arisen, would Pirate teams be allowed to play interracial teams in home games? East Carolina was finding that teams they faced in away games had African-American players. The Board of Trustees addressed the matter and decided on February 1956, two years after Brown v. Board of Education, that East Carolina’s athletic teams would not be allowed to play interracial teams in home games. In doing so, the Trustees cited the school’s charter which stated that East Carolina had been founded for the education of “young white men and women.” The Jim Crow mentality was still very alive, even after Plessy v. Ferguson had been overturned and segregation in educational facilities declared unconstitutional.

More cognizant of the need to comply with the Brown v. Board decision, the state legislature in 1957 approved a new charter for East Carolina as well as eight other state-supported schools, eliminating language of racial segregation. Reacting to this, the ECC Board of Trustees went on record expressing their regret over the revised charter. However, the following year, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, including an African-American bass player, came to campus and performed in Wright Auditorium before an enthusiastic if surprised audience. Responding to student requests for permission to bring more African-American performers to campus, the Trustees decided to allow it, provided that the president of the school approved of the performers. Lines had been crossed and policies changed, setting the stage for the next step in campus desegregation, admission of African-American students.

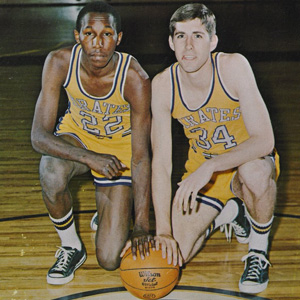

In 1963, Laura Marie Leary, the first African-American undergraduate at East Carolina, enrolled; in Leary’s first year, she was the only African-American on campus. The following year, sixteen additional African-American students enrolled. In 1966, approximately 50 African-Americans enrolled at ECU, among them was Paul D. Scott, the first African-American student to receive a football scholarship. The same year, Vincent Colbert and Marvin Simpson became the first African-American players on the basketball team.

Colbert, who also received an athletic scholarship, was a two-sport star, playing on the basketball and baseball teams. He helped lead the baseball team to back-to-back Southern Conference championship titles, in 1967 and 1968. A pitcher, Colbert tossed nine complete games, the third most in school history. As a basketball player, he averaged over 14 points and seven rebounds per game during his two-year career. After graduation, he played professional baseball with the Cleveland Indians from 1970-1972. In 2009, he was inducted into the ECU Athletics Hall of Fame.

Another outstanding athlete who joined the Pirate basketball team in 1968 was Earl “Earl the Pearl” Thompson, a transfer student from Sue Bennett Junior College. A Greenville native, Thompson had played outstanding ball at C. M. Eppes High School in Greenville under Coach O. E. Meteye. In 1968, Thompson was the leading Pirate scorer, with a 16.9 average. He scored 41 points in a single game, a school record at that time. Thompson’s accuracy with 30-footers and exciting passes reportedly gained him a “tremendous following.” Along with Richard Kier, Thompson served as co-captain of the Pirate basketball team. The contributions of Colbert, Simpson, Thompson and other African-American athletes to Pirate athletics convinced many that desegregation had been a good thing and that more African-American athletes needed to be recruited. The outstanding contributions of Colbert and Thompson in particular did much to dispel still lingering illusions of white supremacy.

One byproduct of the desegregation of athletics was the banning of “Dixie” and Confederate flags at athletic events. When the Student Government Association staged a referendum on March 31, 1969, the overwhelming vote was in favor of banning “Dixie.” No doubt, the contributions of Paul Scott, Vince Colbert, Marvin Simpson, and Earl Thompson to Pirate sports prompted many students to be more considerate about potentially offensive displays, no matter how historic and cultural. The Pirate ethic was to win games and support the team. Replacing “Dixie” and the Confederate flag, new and more robust expressions of Pirate culture emerged, with Pirate flags, buccaneer supremacy, and later “Purple Haze” among other tunes becoming campus favorites.

Sources

- “Earl Thompson, Co-Captain.” East Carolina University Basketball: 1968-1969. University Archives # 40.02.01.12. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N.C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/51012.

- East Carolina College Board of Trustees Minutes, February 22, 1956. East Carolina University Archives # 01-01-22February1956. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N.C.

- “Vince Colbert.” ECU Athletics Hall of Fame. https://ecupirates.com/hof.aspx?hof=28.

Citation Information

Title: Sports Desegregated

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/18/2019