- East Carolina Teachers College

- East Carolina College

- East Carolina University

East Carolina Teachers Training School

On February 9, 1910, the Faculty Assembly approved the formation of a baseball club for young men on campus, as well as athletic programs for women, then the majority student presence. As the student body became decidedly female, the baseball club, despite an impressive start playing local high school teams, vanished. Instead, various forms of athletic activity — tennis, basketball, and cross country walking — emerged as staples.

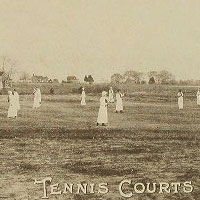

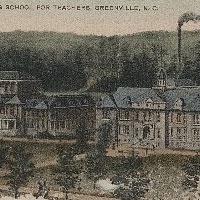

Open acreage on the backside of campus (south side) became athletic fields, with four tennis courts and, later, two basketball courts predominating. Student hikers cut walking trails into the wooded areas south of the campus for hikes covering miles of terrain. By 1918, volley ball courts added to the athletic options. Early drawings of the campus featured a gymnasium on the east end, but that remained a dream realized only with the construction of the Student Activities Building (later Wright Building) in the mid-1920s.

At ECTTS, every student was expected to spend at least one hour per day outdoors engaged in some form of athletic activity. The faculty recognized athletics as “of the highest importance to this student body from the physical, moral and educational standpoints.” Training in athletics was viewed as another dimension of teacher training. For the health and well-being of all, student involvement in athletics was required, as supervised by the faculty athletic committee.

In 1913, the first Athletic Association was organized. Faculty supervision served in the absence of physical education instructor. Basketball was emphasized because its teams involved the largest number of students. Teams were intramural, organized according to year and academic program. Competition on campus climaxed with an annual basketball tournament held on Thanksgiving Day, with the winning team receiving a loving cup. The competition was so popular that another tournament was held in the spring, concluding the academic/athletic year. Competition in volley ball, tennis, and cross country walking also emerged. Tennis was very popular, with the number of courts doubling to eight, reflecting student demand for access to that sport.

Educationally, students were taught the basics of games for all ages, and the importance of athletics in public schools was emphasized. Faculty called attention to the need for playgrounds at schools, especially in rural school settings where public facilities were lacking. From its start, the Training School Quarterly regularly included articles discussing the importance of athletic activity on campus, and in the public schools.

One faculty member, Mabel M. Comfort, was the leading faculty director for the Athletic Association and athletic activities on campus. Herbert Austin, a science faculty, was one of the more successful coaches, coaching the 1915 senior team to a championship victory in the intramural tournament.

During WWI, athletics were emphasized as a necessity for Americans generally, especially in light of health problems that became apparent once the county entered the war. However, in 1918, the Athletic Association suspended its efforts, temporarily, as the ladies on campus were mobilized to pick cotton to raise money for the “United War Work Fund,” with some funds going to purchase of Liberty Bonds and others to the Red Cross. “Refugee babies” were also supported with student earnings from picking cotton.

Following WWI and the renewed emphasis on the need for higher standards in teacher education, East Carolina was rechartered as a teachers college, ECTC. The early emphasis on athletics and the importance of athletic activity blossomed during the next stage of the school’s development, with the appearance of a gymnasium facility, as well as an array of new sports that catered, once more, to the return of male students to the campus in the mid-1930s.

Sources

Comfort, Mabel M. “Organized Out-of-Door Sports,” Training School Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4, January, February, March

(Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton Printing Co., 1915), pp. 220-223.

“School Activities: Athletics.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4, January, February, March 1916, p. 347.

“Movement on Foot for Erection of Gymnasium.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 2, July, August, September, 1914, pp. 110-111.

Wood, Thomas D. “Fit to Fight- Are You a Slacker?” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, October, November, December, 1918, pp. 236-240.

“School Activities: Athletic League.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, October, November, December, 1918, p. 287.

“United War Work Campaign.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, October, November, December, 1918, pp. 289-290.

“School News: Cotton Picking the Fashion.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, October, November, December, 1918, p. 292.

“Supporting a Refugee Baby on Cotton Money.” The Training School Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, October, November, December, 1918, p. 292.

East Carolina Teachers College

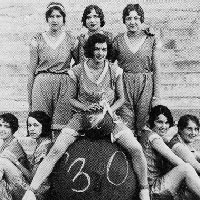

Major changes in athletics occurred during the Teachers College era, 1921-1952. The opening decade continued trends from the Training School years, with basketball, tennis,

and cross-country hiking, along with courses in exercise and team sports dominating the athletics scene. Women constituted, as they had for most of the Training School era,

the student body. Athletics were intramural, and geared toward physical fitness, character building, and good sportsmanship.1

Innovations during the 1920s were relatively minor. A new wing was added to the Administration Building (later Old Austin) finally providing a gymnastics space,

the first on campus. Discussions of future building plans invariably mentioned the need for a gymnasium.2 The Teachers College Quarterly, the school’s showcase

publication, continued to feature articles affirming athletics as an important component of teacher education.3 And, as an innovative teachers college, ECTC recognized athletics as an essential dimension of its progressive curriculum.

Along with the Thanksgiving basketball game, the school’s Field Day, held in May, was an important campus event. Field Day students competed in various sports, with the

class winning the highest number of points receiving the school’s athletic cup.4 Making things more interesting, members of the Athletic Association were also divided into

two groups, the Athenians and Olympians.5 Linking athletics and campus fashion, the ECTC Athletic Association awarded letters or monograms to students who earned sufficient

points through participation in athletics and compliance with health rules.6

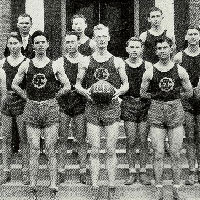

As men began to enroll in the 1930s, things changed profoundly.7 In 1932, a “football group” was organized, but did not play intercollegiately. A men’s “basketball squad” and “baseball squad”

were also organized. A Men’s Athletic Association was established in 1932, prompting the crystallization of a Women’s Athletic Association as an alternative expression of the old Athletic

Association, which had been exclusively female.8 1933 was the first year of intercollegiate football for “the Teachers,” as the men’s teams were first known. The Women’s Athletic Association,

along with the women’s basketball team (which played occasional intercollegiate games), remained prominent. 9

Campus identity and culture began to change in the mid-1930s. The 1934 Tecoan (Teachers College Annual) featured, for the first time, the pirate motif in its frontispiece and marginal illustrations.

Although the athletic teams were not yet identified exclusively as “Pirates,” the suggestion was clearly in the yearbook, even as its “Foreword” introduced the lore of Blackbeard, or “Teachy,

the Pirate,” and his ties to Bath, North Carolina.10 The quickening of the Pirate Nation thus dates conspicuously from the 1934 Tecoan.

1940 marked the beginnings of greatness for campus football. First year coach John Christenbury led the team to an unexpected winning season. The Tecoan praised “Coach John” for initiating a

“Renaissance” in sports on campus. In addition to football, Christenbury coached the men’s basketball team to a winning season.11 The baseball team, led by Gordon Gilbert, also achieved a winning

record. The Women’s Athletic Association added to the vitality of athletics by sponsoring intramural competitions in field hockey, soccer, volleyball, basketball, softball, tennis, bicycling,

hiking, archery, table tennis, croquet, horseshoes, badminton, shuffleboard, and darts.12

1941 brought an even greater achievement for men’s athletics. The football team, led by Christenbury, went undefeated (7-0). It was promptly declared “one of the strongest small college

elevens in the nation,” and “the greatest football combination ever to represent the purple and gold.”13 That year, ECTC also fielded men’s teams in basketball and baseball, though with less

stellar records.

WWII and the prompt enlistment of young men into the armed forces, however, resulted in the reduction of campus athletics. In the 1942-1943 academic year, men’s athletics at ECTC barely

existed. Varsity football essentially vanished. There was no varsity basketball team, and the sport survived only in intramural play. An ad hoc men’s basketball team did play, reportedly,

two games against Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, but lost both. A men’s baseball team remained organized but played no intercollegiate games. The Varsity Club continued in 1942-1943,

but only on the strength of earlier membership. In 1944, intercollegiate sports was largely absent with now revived ECTC basketball being the only team in competition, and it playing teams

such as the Greenville Marines, the Walstonburg All-Stars, the Cherry Point Marines, the Bogue Field Air Raiders, and the Jamesville All-Stars.14

The Woman’s Athletic Association, however, continued as “one of the most outstanding organizations” on campus. In 1942-43, its fund-raising efforts led to contributions to the National Bond

Drive, the Infantile Paralysis Campaign, and the World Student Service Fund. The WAA also organized women’s intramurals on campus, an annual dance, and a trip to the beach. Intramural programs

in field hockey, soccer, volleyball, basketball, softball, tennis, archery, hiking, and individual sports became more important parts of campus life. The WAA also selected “an honorary varsity”

team in each of its intramural sports.15

Following WWII and the return of men to campus in large numbers, male intercollegiate athletics was quickly revived. In 1945, intercollegiate basketball resumed, with a winning season. In 1946,

intercollegiate football was resumed for the first time since the war.16 Yet the most enduring legacy of the late-ECTC era was the ongoing shift away from the “Teachers” identity to the new one,

the Pirate. The latter came to dominate Homecoming parades, male team sports, yearbook covers, and campus culture generally. By 1947, “the fighting Pirates” motif pervaded the campus.17 Nevertheless,

in 1948, the football team had a disastrous 0-9 year. Other men’s teams – basketball, boxing, and tennis – were stronger. The Women’s Athletic Association continued its tradition of organizing

women’s intramural basketball games, now played between dorm-based teams – Fleming, Cotten, and Jarvis.18

The Teachers College era ended with the completion of two major facilities on the southeastern corner of campus occupying the ground where Brewster, Fletcher, the Croatan, Speight, and Rivers

now stand. In 1949, a new football field, flanked with bleachers and commonly referred to as “the stadium,” was completed. Also, a sizable gymnasium was constructed. The gym was subsequently

named for the late John B. Christenbury, who died serving his country during WWII. The impressive on-campus gymnasium and adjoining football stadium elevated athletics to unprecedented heights.

The gym, it should be added, included a new facility on campus, a swimming pool. The latter soon gave rise to East Carolina’s intercollegiate swimming teams, male and female.

New sports also appeared following WWII. Pirate golf emerged, and in 1951, the “Buc linkster” team captured the coveted North State Conference title. Men’s tennis also appeared.19

Pirate baseball became a more deeply rooted dimension of intercollegiate competition at East Carolina with a practice baseball diamond located behind the new gym.

Cheerleaders, male and female, helped maintain school spirit throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s. Although the press commonly referred to ECTC teams as “the Pirates” or “the Bucs” in print,

team jerseys displayed “ECTC” and Varsity Club sweaters still featured a large “T” referring to the first identity of the teams as “the Teachers.” With the coming of men to campus and the

development of men’s intercollegiate sports, the athletic culture of campus had been revolutionized. In effect, East Carolina was realizing, in athletics and well as academics, the co-educational

mission that was part of its original charter. Nevertheless, these developments remained within the confines of the segregated world of higher education, still prevalent in the state and much of

the country at the time.

Sources

1 “Athletic Association,” Tecoan (1923), pp. 101-103.

2 “Editorials: The Building Program,” Teachers College Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 2 (January, February, March 1922) , p. 174. “College News and Notes,” Teachers College Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 4 (July, August, September 1922), pp. 461, 462-463.

3 Ralph Deal, “Athletics in the Rural School,” Teachers College Quarterly, Vol. X, No. 1 (October, November, December 1922), pp. 8-16.

4 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1926), p. 207.

5 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1926), p. 207.

6 “Athletics,” The 1930 Tecoan, pp. 127-131. In 1930, the number was 500. In 1925, it had been 300. “Athletics,” The 1926 Tecoan, p. 209.

7 As late as the 1931-1932 academic year, athletics at ECTC was female, and the Athletic Association was entirely female. Tecoan (1932), pp. 180-186.

8 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1933), pp. 159-168.

9 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1934), pp. 135-142.

10 “Foreword,” Tecoan (1934), pp. 4-8.

11 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1941), pp. 160-165.

12 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1941), pp. 160-171.

13 “Athletics,” Tecoan (1942), pp. 157-58.

14 “Men’s Athletic Association,” Tecoan (1945), p. 113.

15 “Woman’s Athletic Association,” Tecoan (1943), 158-159. Tecoan (1944), pp. 136-141.

16 Tecoan (1947), p. 110.

17 Tecoan (1948), pp. 108-109.

18 Tecoan (1949), pp. 114-129. Tecoan (1945), p. 111.

19 Tecoan (1952), pp. 162-164.

East Carolina College

In the spring of 1951, the North Carolina General Assembly voted to upgrade East Carolina as an academic institution, changing its name (and mission) from that of a teachers

college to that of a four-year liberal arts college. During the ECC years that followed, 1951 to 1967, the school experienced phenomenal enrollment growth, most especially in

its male population. In tandem with this new academic standing and an emerging gender balance on campus, Pirate identity became stronger and more pervasive, especially in

athletics but in virtually all areas of campus life. Just as the 1934 Tecoan signaled the start of the Pirate era, so did the Tecoans from the early 1950s forward reveal the

increasing depth of that identity, with cover after cover featuring an embossed pirate image. Finally, the 1953 yearbook made this campus branding evident in no uncertain terms.

That year, the yearbook abandoned the old and honored title, Tecoan, in favor of one more representing the contagious athletic spirit of the college, Buccaneer. Pirate culture

conquered the campus and much of the community and region, reigning supreme, and almost invariably associated with the athletic prowess of the school.

The early ECC era built upon developments of the late-ECTC era. The new Memorial Health and Physical Education Building (later named after John Christenbury), was dedicated on

January 6, 1953. As before, the student body included a Varsity Club for men, and a Women’s Athletic Association. Football remained the dominant program. Jack Boone was the head

coach, and earned the distinction, within the North State League, of Coach of the Year. Overall, ECC emerged in 1952 within the North State League as a significant competitor,

ending the season in second place, with four victories, one tie, and one defeat. Pirate basketball, as it had come to be known, recorded their most victorious season. Pirate

baseball, also coached by Jack Boone, played well in the North State Conference, with a 12-8 season, finishing second in the conference. Men’s tennis has a winning season with 7-4.

Taking advantage of the new swimming pool in Memorial Gym, an aquatics club was organized. Pirate golf continued prominently, but failed to win the conference championship for the

first time since 1947.1

Memorial Gym became an auxiliary center of campus life. To and from the gym, students enjoyed a scenic walk through the campus arboretum. A fireplace just west of the gym provided a

convenient spot for picnics. As of 1954, ECC had a new team sport, swimming, and a new organization, the “aquanymphs,” making the most of the gym’s natatorium. Most notably, in 1953

Pirate football, led by Jack Boone, won the North State championship, a first for ECC, with a 6-0 conference record. The Homecoming football game drew, reportedly, a crowd of nearly

10,000, and resulted in a Pirate victory over Elon, 45-25.2 The Pirate basketball team also won the North State championship. The Pirates continued to compete well, for the most part,

in the North State League during the later 1950s. In the 1954-55, a men’s swim team was first organized. Ray Martinez was its coach. Martinez also coached the men’s tennis team.

By the late-1950s, ECC had a well-developed Department of Health and Physical Education catering to the curricular interests of ordinary students, as well as to the competitive interests

of those intent on either intramural or intercollegiate sports. It also focused on professional training for students planning to go into the field in teaching.3

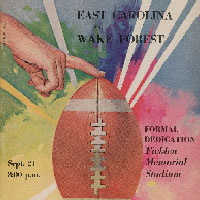

The 1960s changed everything, bringing yet another revolution to campus athletics. First, a new football stadium, the James S. Ficklen Memorial Stadium, was completed in 1963, giving the

college’s football team a premier facility for competition in the North State League. The new stadium also helped ECC gain entrance, in 1965, to in a new and more prestigious athletic league,

the Southern Conference.4 During the early 1960s, Clarence Stasavich (1913-1975), one of the outstanding coaches in Pirate football history, led the ECC team to new heights. Along with a

succession of winning seasons, Stasavich’s Pirate team competed in and won three consecutive bowl games, in 1963, 1964, and 1965. The Stasavich years were a golden period in intercollegiate

football history at ECC. In 1976, Stasavich was inducted into the ECU Sports Hall of Fame.5

During the early 1960s, East Carolina moved away from the Jim Crow system of racial segregation with the enrollment of Laura Marie Leary (1945-2013), the first African-American undergraduate

at East Carolina. By the mid-1960s, athletics embraced the new desegregated order. In 1966, ECC awarded, for the first time in its history, African-American athletes athletic scholarships.

Paul D. Scott was the first to receive a football scholarship. The same year, Vince Colbert, a two-sport star, received an athletic scholarship as well. As a forward on the basketball team,

Colbert averaged 14 points and seven rebounds per game during his two-year career. Most notably, Colbert led the baseball team to Southern Conference titles in 1967 and 1968. After graduation,

he played professional baseball with the Cleveland Indians from 1970-1972. In 2009, he was inducted into the ECU Athletics Hall of Fame.

1966 also witnessed the completion of a major new athletic facility, Minges Coliseum, just west of Ficklen Stadium. Minges, as it came to be known, further defined the emerging athletic

campus south of 14th Street, across from College Hill.6 ECC’s impressive growth and the overwhelming popularity of athletics had long since rendered the east end of the original campus,

the first home of college athletics, sorely inadequate. Furthermore, the east end of campus was needed for new academic buildings meant to accommodate the school’s continuing curricular

growth. With the purchase and development of new land south of 14th Street and adjoining the New Bern highway (later Charles Blvd.), ECC pioneered, in the early 1960s, the beginnings of

what became, most fully in the ECU era, an exceptionally spacious and well-developed athletic campus, featuring new facilities for tennis, swimming, track, football, basketball, baseball,

lacrosse, and soccer. While the appearance of male sports on campus, along with Christenbury gym and College Stadium, had been the revolution of the ECTC era, invigorated Pirate culture,

Ficklen Stadium, Minges Coliseum, and the desegregation of athletics transformed old school athletics at ECC in even more profound ways.

Sources

1 Buccaneer (1953), pp. 155-174.

2 “Sports,” Buccaneer (1954), pp. 162-

3 “Health and Physical Education,” Buccaneer (1958), p. 54.

4 “What’s In a Name? Dowdy-Ficklen,” Daily Reflector (Jan. 9, 2016). James S. Ficklen, president of the E. B. Ficklen Tobacco Company in Greenville, was a longstanding supporter of the college. In 1994, the stadium was renamed the Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium, in honor of a major gift by Ron and Mary Ellen Dowdy

5 “ECU Pirates Hall of Fame.” http://www.ecupirates.com/sports/2016/7/7/hallfame-vince-colbert-html.aspx.

Accessed February 16, 2018. Marvin Simpson and Colbert were the first African-American basketball players at ECC.

6 The building honors the following members of the Minges family: Mr. and Mrs. M. O. Minges and their children Martha Minges Bass, Forrest, Hoyt, John, Max and Ray Minges. M. O. Minges was the

founder of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co. of Greenville. In 1966, John Minges, the president of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company of Greenville, donated $25,000. At the time, this was the largest

single private gift ever received by the college. http://media.lib.ecu.edu/archives/bldg_history.cfm?id=99. Accessed February 16, 2018.

East Carolina University, 1967-present

In the fall of 1967, East Carolina became one of the newest and most dynamic universities in North Carolina. As part of the drive for university status, ECC President Leo Jenkins regularly invited governors, including Terry Sanford, Dan Moore, and Bob Scott, to Ficklen Stadium for football games. By 1967, the new Minges Coliseum, adjacent to Ficklen, became the impressive new home for the basketball and swimming programs. The same year, stadium seating was added to Ficklen’s north side, doubling its total capacity to 20,000. Tennis courts flanked Minges, and on nearby practice fields, lacrosse, track, baseball, soccer, and rugby thrived. While the decision to recognize East Carolina as a university resulted from many factors, the school’s development of a first-class athletics campus prompted the support of many.

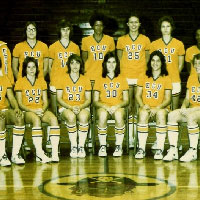

The most revolutionary development in ECU athletics, however, had little to do with athletic facilities and everything to do with student participation. In short, the revolution in ECU athletics occurred with the beginnings of women’s intercollegiate sports at ECU in 1970. No doubt, this was one dimension of the women’s movement on campus, as well as nationwide. At ECU, women’s teams soon attained prominence in athletic competition. For example, during the 1972-1973 season, the women’s basketball team — the “Lady Bucs” or “Lady Pirates” — won the state championship. With an outstanding 19-2 record, the team also competed in the women’s national basketball tournament.1

In the 1970s, men’s sports fared equally well. In 1971, East Carolina won Southern Conference championships in cross-country, swimming, wrestling, and golf. In 1972, the men’s basketball team went to the NCAA tournament, and in 1973, East Carolina won the Southern Conference championship titles in football, wrestling, and swimming. Head football coach Sonny Randall was named the Southern Conference Coach of the Year, and Carlester Crumpler was named Southern Conference Player of the Year.

Yet the major new development was women’s intercollegiate sports competition. In the early 1970s, the ECU Board of Trustees approved a restructuring of athletics on campus, providing for increased funding for women’s athletics and the growth of that program overall. The trustees decided, additionally, to withdraw ECU from the Southern Conference. They also approved expanding the seating capacity of Ficklen Stadium to 35,000. These decisions were meant to take ECU athletic competition to the next level in an effort to preserve the school’s standing as a NCAA Division One Football Institution, a status threatened by continued competition in the Southern Conference.2

A tragic milestone occurred on October 24, 1975: former football coach and then athletic director, Clarence Stasavich, 62, unexpectedly passed away. Stasavich had led the football team to greatness, achieving an impressive 50-27 record in eight years as head coach. He also led the team to three consecutive bowl games. Most credit Stasavich with elevating ECU football to national prominence. The day after his passing, in tribute to his efforts, the Pirates defeated UNC, 38-17, in a historic match between the in-state rivals.3

Catherine Bolton decisively led women’s athletics. As its director, Bolton oversaw the initiation of seven intercollegiate sports for women: field hockey, tennis, volleyball, basketball, gymnastics, swimming, and golf. During her tenure, ECU first awarded athletic scholarships to women. Bolton’s efforts were empowered by Title IX of the Education Amendments enacted in 1972 prohibiting sex discrimination at any school receiving federal financial aid. Rightly, Bolton commented that in the wake of Title IX, funding for women’s athletics at ECU and other institutions receiving federal aid would have to increase. She added, “Title IX means changing in two or three years. Without it the changes would take 20 years.”4

As with men’s teams, women’s competed in Minges Coliseum, and practiced on the grounds surrounding Ficklen and Minges. A softball team, added in the 1977-78 season, promptly achieved a winning record, as it did in 1978-1979, going 18-12. By the end of the 1981 season, the softball team had a record of 44-7, becoming the first in East Carolina athletics history to achieve a 40-win season. For much of that season, the Lady Pirates were ranked number one in the country.5

Head coach Cathy Andruzzi led the 1980-1981 women’s basketball team (23-7) to their first appearance in the Associated Press Top 20 poll, and their first trip to the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) regionals, plus two in-state victories over NC State. The same year, the Lady Pirates outdrew the men’s team by 22,000 to 19,800 in annual home-game attendance. In 1981-1982, the Lady Pirates finished with a 17-10 record, and played in the first women’s NCAA regional tournament.6 While at ECU, Andruzzi won national fame for her Cathy Andruzzi Show, the nation’s first weekly television and radio show hosted by a women’s basketball coach.7 During her six seasons, 1978-1984, Andruzzi’s teams won 105 games. She was inducted into the ECU Athletic Hall of Fame in 2000.

In the 1970s, Christenbury Gym emerged as the center of campus intramural programs, offering students a variety of sports opportunities including flag football, golf, team tennis, badminton, softball, volleyball, free throw shooting, basketball, swimming, track and field, soccer, and team handball. By the 1980s, ECU had one of the fastest growing Sport Club Programs on the East Coast, with clubs in archery, Frisbee disc, karate, lacrosse, racquetball, rugby, soccer, surfing, and handball.8 In 1982-1983, the school celebrated its fiftieth year of intercollegiate competition, one crowned by the football team’s 7-4 record. Both the men’s and women’s basketball teams had winning seasons. The baseball team added to the glory, finishing the year with their twelfth consecutive winning season. The Lady Pirates softball team captured the state championship and played in the National Invitational Softball Tournament.9

In 1994, Ronald and Mary Ellen Dowdy donated $1 million for stadium renovations, prompting the ECU Board of Trustees to rename the facility Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium. In 2009-2010, the north and south sides were joined with a 7,000-seat addition to the east end. Currently, Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium is undergoing a $60 million renovation, providing for 1,000 premium seats, a new club level, suites and loge boxes, and premium parking. A new press box, replacing the current one dating from 1977, is planned. Overall seating capacity will remain at approximately 50,000.10 The stadium has served as ground zero for Pirate football greatness, as led by excellent coaches such as Sonny Randall (1971-1973), Pat Dye (1974-1979), Steve Logan (1992-2002), Skip Holz (2005-2009), and Ruffin McNeil (2009-2015).

Minges Coliseum underwent a $12 million renovation in 1994-1995, upgrading the arena area into one of the finest on-campus basketball facilities on the East Coast. In honor of the generous support Walter and Marie Williams provided for the Education Foundation (Pirate Club) and for athletic scholarships, the arena space was named the Williams Arena at Minges Coliseum.11

From the 1990s on, this unprecedented expansion of campus athletic facilities thus amounted to yet another ongoing, revolutionary dimension of ECU athletics. By the spring of 2005, Harrington Field, the old site of ECU baseball, had been transformed into an impressive, state of the art facility, Clark-LeClair Stadium, named after Keith LeClair (1966-2006). In five years coaching Pirate baseball (1998-2002), LeClair achieved a 212-96 overall record, four conference championships, and competition in four consecutive NCAA tournaments.

In 2011, a brand-new 1,000-seat, state of the art softball stadium adjacent Clark-LeClair Stadium opened with a solid victory over UNC-Wilmington. The softball stadium was one of the premier additions to the emerging athletic campus, as redesigned by athletic director, Terry Holland. Adjacent to it, the new Bate Foundation Track and Field Facility was completed in 2011. Next to that, a new 1,000-seat soccer stadium was built. Each of the new facilities echoed the design of Clark-LeClair, giving the sports complex a unity in architecture as well as purpose. In 2015, in recognition of Holland’s transformative efforts in elevating every dimension of ECU athletics, the complex was named the Terry Holland Olympic Sports Complex. As the home to non-revenue sports programs (softball, soccer, and track), it serves as an impressive statement of ECU’s commitment to a range of competitive athletic programs.12

This commitment was earlier made evident with the new North Campus Recreational Facility featuring eight multipurpose fields and a six-acre lake with a sandy beach for canoeing and kayaking. More proximate the main campus and just west of the Holland Sports Complex, the Blount Recreational Sports Complex, completed in 1998, also provided students with 21 fields for intramural competition in softball, football, and soccer. The Blount Sports Complex and the North Campus Recreation Facility in turn expanded on the main campus Student Recreation Center, one of the major contributions to athletics made during Chancellor Richard Eakin’s tenure in the mid-1990s. The Student Recreation Center, often showcased on campus tours, features basketball courts, a climbing wall, a track facility, weight and fitness training facilities, plus indoor and outdoor pools.

Another revolution in ECU athletics occurred at the curricular level. In addition to longstanding general education requirements related to physical fitness, ECU presided over the development of various academic programs focused on the scholarly study of athletic activity and human health. The Department of Health Education and Promotion in the College of Health and Human Performance, for example, offers a BS in athletic training, as well as a MA and MAEd in Health Education. The Department of Kinesiology has an array of degree programs, undergraduate and graduate, catering to student interests in exercise physiology, sports studies, health fitness, kinesiology, and physical fitness. That department also has a PhD program in bioenergetics and exercise science. ECU athletics has thus become, more than ever before, an integral part of the campus, community, and curriculum, graduate and undergraduate.

Sources

1 “East Carolina Through the Years,” Buccaneer (1974), pp. 52-53. “And Speaking of Women …,” Buccaneer (1973), pp. 102-103, Part 2, pp. 12-18. Diane Taylor, “Women’s Athletics Achieves Status, Works Towards Title IX Compliance,” Buccaneer (1976), p. 194.

2 “ECU Pirates Leave Southern Conference,” Buccaneer (1976), pp. 152-153.

3 “In Memory of a Great Man,” Buccaneer (1976), p. 160.

4 Diane Taylor, “Awards 7 Scholarships – First Time in ECU History,” Buccaneer (1976), p. 195. At the time, male athletes received a total of 200 scholarships.

5 “Wind ‘Em Up, Ladies,” Buccaneer (1979), p. 250. William Yelverton, “Swing At The Top,” Buccaneer (1981), p. 200.

6 Jimmy DuPree, “Beating the Odds,” Buccaneer (1981), pp. 162-169. Mike Hughes, “An Uphill Battle,” Buccaneer (1983), p. 193.

7 http://www.cathyandruzzi.com/profile/. Andruzzi left ECU to become owner-operator of six successful Domino’s Pizza franchises in New Jersey. http://globalsportsbusiness.rutgers.edu/people/directors/39-catherine-andruzzi

8 “The Games People Play,” Buccaneer (1979), p. 97. “Intramurals,” Buccaneer (1983), p. 247.

9 “Putting It Together,” Buccaneer (1983), p. 7. Ken Bolton, “A Golden Tradition,” Buccaneer (1983), p. 223. Ken Bolton, “New Life in the Fast Lane,” Buccaneer (1983), p. 226.

10 https://news.ecu.edu/2018/01/12/athletic-renovations-promise-benefits-for-students-fans/.

11 http://www.ecupirates.com/facilities/?id=12.

12 Steve Tuttle, “From the Editor: Olympic Sports Have New Home,” East: The Magazine of East Carolina University, vol. 9, no. 4 (Summer 2011), p. 2. J Eric Eckard, “Olympic Sports Have New Home,” East, 9/4, pp. 22-27.