In the summer of 1962, East Carolina admitted 15 African Americans to summer school, including 13 graduate students and two undergraduates, alongside over 3,000 white students. This was a historic first for the institution. Originally chartered as a Jim Crow campus for whites, East Carolina’s first half century, 1907-1957, had brooked no exceptions in admissions even while allowing, as a “progressive” school, condescension and mockery toward others. Yet after its charter was amended in 1957 and its racially specific mission of educating “while men and women” eliminated, East Asian students — Chinese, Korean, and Japanese — were admitted as the first non-white students in East Carolina’s history, quietly yet effectively crossing the now obsolete Jim Crow line in profoundly unprecedented ways. Broadmindedly, the campus newspaper ran coverage about these new students and their seemingly exotic stories.

Yet in the eyes of many, including the federal government, until African Americans were enrolled, East Carolina would be deemed a segregated campus in violation of the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregation unconstitutional. With the enrollment of 15 African Americans in the summer of 1962, ECC continued a slow but sure course toward compliance with the high court’s ruling. In making this move, it followed UNC, Woman’s College in Greensboro, and North Carolina State College (now, NCSU) in Raleigh. Among private schools, Wake Forest, Duke, and Davidson had already allowed African Americans to enroll. East Carolina was, then, the last major campus in North Carolina to desegregate, but, notably, the first in the eastern part of the state.

1962 was not, however, the truly historic year: statewide media coverage, based on college news releases, quoted Pres. Leo Jenkins (1913-1989) as remarking that 1962 was nothing new: the year before, in the summer of 1961, East Carolina had enrolled a “handful” of African Americans in a two-week graduate seminar,” making 1961 the more historic date. Still, the summer of 1962 was important: it marked the first time African Americans had been admitted for a full six-week term in summer school, not just a two-week seminar.

In neither year did ECC celebrate the African Americans enrolling. With surprising silence, note was not even taken, simply for the historical record, of the names of the African American students. Extant records only relate that “Negroes” were allowed admission. Yet some details were released: the 1961 “students” were in-service teachers in African American schools in Greenville’s still segregated public school system taking classes to renew their teaching certificates. Earlier, African American teachers, even those living in Greenville, had to travel as far as Greensboro for such coursework because East Carolina, the proximate and seemingly logical option, was by charter a white school. College officials, when asked about the names of the African American students, replied that they could not ascertain them because “registration forms … [did] not include any designation of race.” The forms, apparently a carry-over from Jim Crow times, assumed that the student body would be of homogenous racial identity.

Then again, it could be that ECC refused to release the identities of the students because it was concerned about their safety, fearing that if names were released publicly, the individuals and the school might become targets of racist backlash. Whatever the case, no known documents relate who the first African American students were. Along similarly sketchy lines, news reports added that in addition to the 1961 summer seminar in Greenville, some African Americans had “attended extension courses conducted by the college at Camp Lejeune and Goldsboro,” though again without specifying when, exactly, this had occurred or by whom.

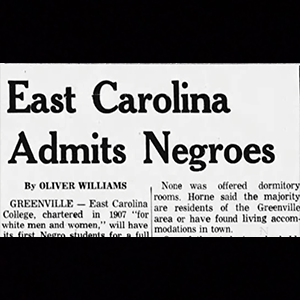

In mid-June 1962, coverage of these developments at ECC appeared in newspapers statewide. The News and Observer presented the most detailed and fairest coverage, frontpage, under the headline, “East Carolina Admits Negroes.” It noted that earlier African Americans had applied to ECC but “failed to meet admission requirements.” The N&O did not hint that East Carolina had lowered its academic standards for the sake of enrolling African American students. In fact, in noting previous rejections, it suggested the opposite. Nevertheless, several newspapers — including the Rocky Mount Telegram, the Burlington Daily Times-News, and the Asheville Times — reported, in their headlines, that ECC had “lowered bars” to facilitate enrolling African Americans, hinting that academic standards had been lowered along with exclusionary tactics meant to maintain Jim Crow segregation de facto if not de jure.

The East Carolinian ran a frontpage article on the 1962 summer session and its record enrollment of 3,111 but made no mention whatsoever of the school’s enrollment of African American students. Pres. Jenkins, as quoted there, only related that many of the summer session students were following an accelerated program for graduation in three years rather than four.

The News and Observer quoted Dr. John H. Horne (1914–2007), the ECC registrar, at length. According to Horne, the majority of the 1962 students were teachers already holding undergraduate degrees taking coursework to renew their certificates. Two undergraduates were admitted for summer work, but they intended to transfer to other colleges in the fall. Some of the 15 African American students were admitted for the full summer term while others were registered for a two-week workshop. Those enrolled for graduate work were admitted provisionally and given examinations to establish that they met entrance requirements. Examinations were not required for those enrolled in the two-week course. ECC reportedly required of all students “admissions tests for both graduate and undergraduate work.”

Horne added that the African American students were day students, living off campus. Reportedly, none was offered dormitory accommodations. Horne explained that the majority were residents of the Greenville area or had found accommodations in town. Their registration had proceeded smoothly. According to Horne, one of the students had a degree from a Maryland college and had taken courses at North Carolina State College but registered at East Carolina to take “reading courses not available at State.”

Although ECC’s admission of African American students is today recognized as a progressive victory for the cause of social justice, at the time even among its advocates, it was viewed with reticence as a pragmatic alternative that ultimately East Carolina had no real choice but to go forward with. After ECC’s charter was amended in 1957, the school’s board of trustees went on record expressing regret over the change yet simultaneously recognizing that thenceforth there were no legal grounds for refusing qualified African Americans enrollment.

Even as they affirmed a reluctant intent to comply, the trustees stipulated that the college president should call a full meeting of the board if qualified applicants did indeed apply. Such a meeting occurred May 27, 1961. It was the last before, that summer, the first African Americans enrolled in a two-week summer workshop on campus, and the one at which the board consented to what followed. Although profoundly consequential, the academic moment was so veiled in silence if not secrecy — again, presumably issuing from worries about school and student safety due to possible backlash — that the identities of the African Americans enrolled remain a mystery, anonymous to history.

One account of the administrative mentality at ECC is found in a letter, dated May 3, 1961, written to a college trustee, Elizabeth S. Bennett (1895–1990), by Pres. Jenkins discussing a matter on the May 27, 1961 agenda: applications from “highly qualified Negro students, some of whom have A [teaching] certificates in North Carolina.” Jenkins’ last remark indicating that some applicants were in-service teachers who held college degrees, clearly implied that they could not easily be denied admission. Jenkins added that discussions with other trustees including board chair, Robert Morgan (1925–2016), Henry Belk (1898–1972), Herbert Waldrop (1895–1966), Henry Oglesby (1908–1985), and Charles H. Larkins (1906–1975), as well as “the Vice President of the University of Tennessee and some of our government officials in the state,” led him to conclude that “the only thing we can do is to admit them without a lot of fanfare, making the procedure as routine as possible and explain to the students that their cooperation will be needed.” He further noted that “the only alternative, according to one of the lawyers on our board, is that of throwing it to the courts, with the accompanying publicity and losing the case in short order.”

Jenkins observed that “the second approach would be considered a challenge to the sources where integration is being pushed and an attempt would doubtless be made to send large numbers of Negroes here after they won a victory.” He acknowledged that he, as president, would “carry out the wishes of the board in this matter,” but recommended “the first proposal, admitting only a few highly qualified applicants, without publicity.” Jenkins advised Bennett that “it may be wise not to discuss this with anyone, for I am most anxious to have no newspaper hassle and no discussions of this until the board has an opportunity to discuss it and make a decision.”

Jenkins’ letter to Elizabeth Bennett echoed thoughts found in another letter, this one by trustee Henry Belk, longtime editor of the Goldsboro News-Argus, to Jenkins dated May 2, 1961, the day before Jenkins’ letter was written to Bennett, just as the ECC board stood at the crossroads of racial change. In his letter to Jenkins, Belk, more forcefully, explained,

“… the college cannot much longer refuse to admit non-white students who fully and completely qualify. As you know, State College [now, NCSU], the University at Chapel Hill, and Woman’s College [now, UNC-Greensboro] have granted such admissions for the past few years.….

We would be doing only what others are doing to put East Carolina quietly and without fanfare into the new stream. If we do not so act we shall in due time be the object of attention which might cause much more repercussions and reactions than admitting a few qualified ones.

There is every evidence from Washington that regulations concerning discrimination will be carefully observed.… A policy of barring non-whites may even see the college denied aid in some fields.

The board is not authorized under the charter to make … [any other] decision. The ban on other than white students was removed under the charter adopted when the Higher Board reorganization was put through. You will recall that originally the charter specified the college was for ‘white’ students. When the new charter was passed by the Legislature, it evidently was anticipated that the college should be in a position to act as wisdom indicated.”

No other trustee went on record, in writing, supporting admission of qualified African American students as forcefully as did Belk. The similarities in Jenkins’ letter to Bennett and Belk’s letter to Jenkins suggest that in advance of May 2-3, when the letters were written, Belk and Jenkins had discussed the matter privately. While pragmatic in argument, their views should not be discounted: the two understood that desegregation would possibly prompt backlash and that to secure solid support for the decision, practical reasoning would be most effective.

The next step, from summer school to the regular academic year, was orchestrated by Dr. Andrew A. Best (1916-2005), a local African American physician and friend of Pres. Jenkins. Best later related, in an oral history interview, his discussions with Jenkins, from “the early 60s,” of the need to desegregate East Carolina. Rather than admitting African American teachers to summer school classes, Best was thinking that East Carolina needed a full-time degree seeking undergraduate to lead the way forward. According to Best, Jenkins was supportive but concerned about the student’s ability to perform academically. Best assured him that he knew, through educational programs that he led weekly for young African Americans in eastern North Carolina, hundreds of qualified students who could meet the challenge.

When Jenkins voiced concerns about the possible negative reactions on campus, Best, no stranger to bigotry, assured him that he had in mind a perfect candidate for the challenge: a young lady, Laura Marie Leary (1945–2013, married name, Elliott), whose family lived 18 miles south of Greenville. Best told Jenkins he had already spoken with Leary’s father and had his backing. Best added that he would provide locally whatever support Leary needed off-campus to make her time at East Carolina as successful as possible. Swayed by Best’s proposal, Jenkins asked Best to have her apply. In the fall of 1962, Laura Marie Leary became East Carolina’s first full-time degree-seeking African American undergraduate. In 1966, she graduated with a major in business administration, thus becoming East Carolina’s first African American to complete an undergraduate degree.

Laura Marie Leary’s time at East Carolina later came to be well-documented, especially through a 2008 oral interview conducted by ECU professor of history, Dr. David Dennard. And, her contributions to ECU history were celebrated at the 2012 Homecoming marking the fiftieth anniversary of East Carolina’s desegregation. Yet sadly, during her years on campus as a student, Leary recalled that she never felt welcome. And while statewide newspapers had readily covered the first African Americans, nameless though they were, admitted at East Carolina, when Leary, a profile in courage, enrolled as East Carolina’s first full-time undergraduate, there was neither news coverage of her presence nor of her historic role as a leader contributing to a more diversified and inclusive campus. Yet at least this time, her name was recorded, and pictures of her included in the Buccaneer, leaving sufficient records for the fuller story to be eventually told and her pioneering role in the challenging process of East Carolina’s desegregation documented and celebrated before her passing in 2013, the year after her return to campus for Homecoming when she was honored as a pivotal leader in East Carolina’s history.

Sources

- “12 Negro Pupils Sign to Attend Classes at ECC.” Charlotte Observer. June 13, 1962. P. 9. https://www.newspapers.com/image/619989239/?terms=ECC%20Negro%20summer%20&match=1

- Belk, Henry. “Henry Belk correspondence [to Dr. Leo Jenkins] about ECC Integration, 1961.” Records of the Chancellor: Records of Leo Warren Jenkins. University Archives # UA02.06.10.35. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/62371

- Best, Andrew A. “Oral History Interview with Andrew Best, April 19, 1997: Desegregating East Carolina University.” Interview R-0011. Karen Kruse Thomas, interviewer. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007). Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection. Wilson Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/R-0011/excerpts/excerpt_7154.html

- Brown, Ben. “Integration Set in 17 Systems.” Durham Sun. August 25, 1962. P. 2.

- East Carolina College Board of Trustees minutes, November 12, 1957. University Archives # UA01.01.01.01.04. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/10262

- East Carolina College Board of Trustees minutes, August 9, 1957. University Archives # UA01.01.01.01.04. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/10260

- “East Carolina College Lowers Bars to Negroes.” The Bee (Danville, Virginia). June 13, 1962. P. 13C.

- “ECC Enrolls Several Negroes.” Winston-Salem Journal. June 13, 1962. P. 9.

- “ECC Lowers Bars on Negro Students.” Rocky Mount Telegram. June 13, 1962. P. 1.

- “ECC Lowers Racial Bars to Students.” Burlington Daily Times-News. June 13, 1962. P. 8A.

- “ECC Opens Its Doors to Negroes.” Durham Sun. June 13, 1962. P. 28.

- “ECC Registers 12 Negroes.” Greensboro Daily News. June 13, 1962. P. 12.

- “First Summer Session Term Reaches 3,111 Enrollment.” East Carolinian. June 26, 1962. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/38761

- Jenkins, Leo W. “Letter from Leo Jenkins to Elizabeth Bennett.” May 3, 1961. ECU Digital Collections. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/23530

- “Laura Marie Leary.” 1966. University Archives # UA50.01.02.14. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/10270

- “Laura Marie Leary Elliott Oral History, October 17, 2008.” Dr. David Dennard, interviewer. University Archives # UA95.14. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/61825

- “Negro Students Gain Admittance to East Carolina.” Durham Morning Herald. June 13, 1962. P. 3.

- “Negro Students Register Quietly at East Carolina.” Greensboro Record. June 13, 1962. P. 15.

- “Racial Bars Are Lowered At ECC.” Asheville Times. June 13, 1962. P. 28.

- Williams, Oliver. “East Carolina Admits Negroes.” News and Observer. June 13, 1962. Pp. 1, 2.

- Zachary, Kristin. “History Maker: Laura Marie Leary, East Carolina’s first full-time Black student was a ‘mother hen’ for others.” ECU News Services. https://news.ecu.edu/2021/02/01/history-maker-laura-marie-leary/

Additional Related Material

Citation Information

Title: East Carolina's First African American Students

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 05/08/2023