On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel, in Memphis, Tennessee, just blocks away from the Mississippi River. In the months prior, Charles Davis, an African American junior from Wilson, had emerged as the leader of student organizations opposing racial discrimination at East Carolina. Davis’ non-violent opposition to racial discrimination was in the tradition of the Greensboro Sit-In of February 1960 as well as the teachings advocated by Dr. King. Immersion in anti-racist activism forced Davis to drop out in the summer of 1968, but he had already become a campus legend, setting an example of courageous leadership in opposition to the multifaceted expressions of Jim Crow culture all too evident to the black student body. The following year, a new generation of leaders emerged – including Johnny Williams, William Lowe, and Benjamin Currence – continuing more aggressively Davis’ efforts toward establishing decency and respect for all on campus.

Earlier, the summer of 1967 shocked much of the nation as race riots erupted in Newark and then Detroit, in both cases occasioned by police brutality. New levels of activism ensued across the country, with young African Americans ready for immediate change protesting racial injustice and discrimination. Yet at East Carolina, one sports columnist continued to publish his thoughts in the East Carolinian, the “Sports Lowe Down,” with a Confederate flag flying over a Civil War-style cannon as his logo. At sports events, students waved Confederate flags, some dressed as Confederate soldiers, and most responded with spirit to band performances of “Dixie.”

Davis’ activism is well-recorded in the East Carolinian. In a letter published in the “ECU Forum” section, January 9, 1968, signed Charles Davis, Chairman, Negro Students Grievance Committee, Davis opened with an explanation: “With much regret, the Negro students of this University feel that it is necessary that we bring to your attention some of the racial discriminations that exist on our campus.” He continued, “A Negro should not be called a n— or a Negra. There should be equal treatment in the placement of students in housing …. Equal treatment should be given when serving students in the University Union Soda Shop and establishments downtown. There should be elimination of discrimination in classrooms. There should be no harassment from policemen on and off campus, regardless of … race, by students and faculty.”

Davis also questioned the obsession with “Dixie,” remarking, “Negroes have wondered why ‘Dixie’ is played at each game, basketball and football. We have been told that to play ‘Dixie’ is a tradition. But we asked a tradition of what? ‘Dixie’ to us carries reference to slavery and the Old South. The ‘Old South’ is dead, and has been dead for 100 or more years! This is a new century and a new time. New centuries call for changes.” He concluded with a plea for solidarity, stating “We ask for the support of the students and faculty to help us eliminate our grievances if they believe racial discrimination is wrong.”

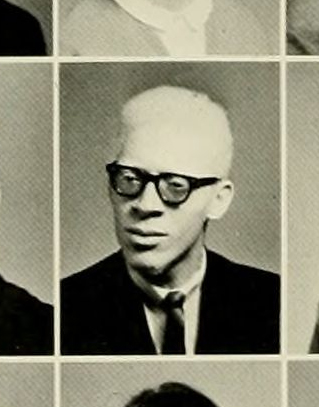

Two days later, on January 11, 1968, the East Carolinian ran a front-page article entitled, “Negro Committee Maps Plans To Stop Race Discrimination.” Atop the article was a picture of the Negro Students’ Grievance Committee including Bernadine Smallwood, Johnny Williams, Charles Davis, Janice McNeil, and Corrietta Hill. The purpose of the newly formed committee, according to its chair, Davis, was “to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination to the extent that we are students at East Carolina University and not Negro students.” Davis further explained “The Negro students on this campus reached the point where they decided it was time to stand up for themselves and make known to the student body problems of discrimination that exist on our campus.”

According to Davis, the committee had already submitted a list of grievances to President Leo Jenkins. In response, Jenkins “said he would cooperate with us as much as possible in dealing with our problems.” Davis added that the committee planned “to work … through the Administration, faculty, SGA, and the student body as a whole. We are appealing to all campus organizations and the student body in general to support us in our efforts to eliminate problems of racial discrimination on our campus.” Davis also stated “We anticipate having some demonstrations which will be non-violent by intent.” He affirmed that the committee would request that the administration grant permits for such demonstrations.

Sharing the top of the front-page, another article, “SGA Approves Student Race Relations Board,” reported that the SGA, recognizing the growing problem on campus, was in the process of establishing a committee that would “create a channel whereby racial groups can present their problems, requests, and suggestions.” Steve Moore, SGA president, noted that the Race Relations Committee would give “the newly organized Negro Grievance Committee and other organizations representing the interests of minority groups on campus” a way to communicate and seek solutions. The lead editorial on the following page commended the SGA for its “recent creation of the Race Relations Board.”

The lead story in the February 1, 1968 East Carolinian, “Negro Committee Advocates Action,” reported on a presentation by the Negro Grievance Committee to the SGA at which Davis, the spokesman, explained that “discrimination exists in the classrooms and among students, the faculty, and the administration.” Davis added, “We have tried to work as much as possible with the school administration but there seems to be a communication breakdown. We have not been taken seriously.” Once again, Davis expressed disapproval of the display of the Confederate flag and the performance of “Dixie.” The latter, he said, “brings up [the] sentiment of racism.” Davis also asked the SGA to “bring about a course in Negro history … [and] increase the number of books in the library by contemporary Negro authors.”

In another letter published in the “ECU Forum,” Davis remarked that ECU’s impressive rapid progress had somehow “neglected to include elimination of racial discrimination on its campus.” He added “Racial tension has drastically increased with the increased number of Negroes attending ECU.” In response to this, “the Negro students have organized to gain equality.” Davis asserted that the problem reached the upper tiers of the administration with one supposedly remarking, “If you don’t like it here, you know what you can do.”

Davis also reported insults, by campus police toward “Negro girls at a recent athletic event.” He even singled out President Jenkins for, in the view of African American students, not doing “his share to eliminate the discriminatory practices….” Davis added that actions taken by students in the absence of leadership from the administration have led to “increased counter-action by the white student population and, in some cases, by the faculty and administration,” noting that “The Negroes feel that this situation is sure to culminate in undesirable consequences for all who are involved.” He added “plans are being made to petition an investigation by federal authorities.”

In the same issue, another letter, submitted by Graham Jones, reported that at a recent basketball he had attended carrying a Confederate flag, one of the “Baby Bucs,” Tyrone Wyche, had asked if he might “salute the Stars and Bars,” but then spat on the flag instead. Jones added that while Wyche might be taller than most, that “eventually these students will have to look down to see you.” Clearly, rhetoric was escalating.

In the February 20, 1968 East Carolinian, Dr. Andrew Best, a local physician and chair of the Pitt County Inter-Racial Committee, voiced his support for the Racial Grievance Committee, acknowledging that there were considerable problems of racial discrimination at ECU. Best stated that they were “so immense that only through teamwork can we hope to find solutions.” While an impressive endorsement, little changed as a result of it.

One significant outgrowth of the Racial Grievance Committee during the spring quarter of 1968 was SOULS (Society of United Liberal Students). Charles Davis was its first president; John Williams, vice president; Kenneth Gallaway, treasurer; William Lowe, parliamentarian; and Luther Moore, sergeant at arms. Davis stated that the purpose of the organization was “to promote better overall conditions and relationships within the city of Greenville for all people with special emphasis on the Negro.” In addition to voicing opposition to racial discrimination on campus, SOULS contributed to the community by working on black voter registration and supporting the political campaigns of African American candidates such as gubernatorial contender, Reginald Hawkins.

In his final letter published in the “ECU Forum,” Davis struck a spiritual chord, stating “it is through faith and brotherhood that we engage in this campaign, based on the assumption that through Christ we can help our people here on earth.” Davis thus echoed recent remarks by Pres. Jenkins suggesting that everyone “rise above the differences in race and creed through the spirit of Christ.” Davis added that SOULS was working on getting the “disadvantaged Negro” registered to vote, and asked the faculty and students to volunteer “to help our fellow man through Christ as the President of this great institution of learning has requested.”

Following Davis’ departure from campus in the summer of 1968, Williams succeeded him as president of SOULS. As things turned out, the SGA Committee did little to improve things. Making matters worse, The Rebel, a campus publication known for its occasional penetrating critiques of social issues, offered a somewhat supportive spoof of the Racial Grievance Committee’s complaints about “Dixie” by noting that the “ECU Administration Grievance Committee” had offered its objections to Bob Dylan’s latest, “The Times They Are a-Changing.”

And, in May, the SGA Special Events Committee announced that the theme of Homecoming 1968 would be “Mardi Gras: Mississippi Carnival,” encompassing “not only Mardi Gras but Showboat, Southern Plantation, minstrel, in short anything that may be touched by the Mississippi.” That fall, with Homecoming, the East Carolinian included a front-page watermark with a Colonial Reb-like figure holding a drink with a Confederate flag atop its stirrer. On page two, an editorial, “Southern Tradition Prevails,” praised ECU as “the epitome of the best blending of Old South spirit with modern growth.”

Shortly after, an English instructor, Edward A. Abramson, published remarks in the “ECU Forum” arguing that the “Life on the Old Mississippi” Homecoming theme had “showed an appalling lack of sensitivity on the part of those responsible for it.” Abramson noted one float in the Homecoming parade included a black-faced student serving white Southern gentlemen drinks, and asked how “the group of black women watching the parade opposite me felt about that. What went through their minds?”

Abramson might well have asked how ECU could celebrate Homecoming with the “Life on the Old Mississippi” theme the same year Dr. King had been shot to death just blocks away from the same river? Despite his courageous efforts, Charles Davis’ earlier pleas for cooperation in opposition to racial discrimination had apparently fallen on all too deaf ears, virtually fating 1969 to be a very different year at ECU.

Sources

- Abramson, Edward A. “Shade of Difference.” East Carolinian. November 19, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39380

- Anthony, Ivorie. “SOULS take action.” Fountainhead. November 3, 1970. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39504

- Atkins, Jerry. “Racial Riots.” East Carolinian. July 27, 1967. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39009

- Bijus, M. “‘Rebel’ Searches For Answer To Poverty And Ignorance.” East Carolinian. November 16, 1967. P. 5. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39316

- Bijus, M. “29th Issue Of ‘Rebel’ Excites EC Campus.” East Carolinian. November 16, 1967. P. 5. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39316

- “Charles E. Davis.” Buccaneer. 1966. P. 436. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15317

- “Charles E. Davis.” Buccaneer. 1967. P. 271. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15318

- “Charles E. Davis.” Buccaneer. 1968. P. 420. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15319.35

- “Charles E. Davis.” Date: June 2, 2014. Crossing the Tracks: An Oral History of East and West Wilson, North Carolina.” Willis N. Hackney Library. 400 Atlantic Christian College Dr., NE, Wilson, N.C. 27893. https://barton.libguides.com/crossingthetracks/interviews/charlesedavis

- “Curfew Maintains Peace.” East Carolinian. April 18, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39343

- “Daniels Announces Mississippi Theme for ’68 Homecoming.” East Carolinian. May 16, 1968. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39351

- Davis, Charles. “Think.” East Carolinian. February 1, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39328

- Davis, Charles. “Civil Injustice.” East Carolinian. January 9, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39321

- Davis, Charles E. “S.O.U.L.S.” East Carolinian. May 2, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39347

- Hadden, Whitney. “REBEL Satire Spoof Achieves Modest Level Of Success.” East Carolinian. March 19, 1968. P. 4. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39338

- Hart, Jack. “Dr. Wright Discusses Black Power Movement.” East Carolinian. November 9, 1967. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39315

- Howard, Marion. “Federal Case.” East Carolinian. February 1, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39328

- Howard, Marion. “Race Relations Committee?” East Carolinian. March 27, 1969. P. 8. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39405

- Jones, Bev. “Negro Committee Advocates Action.” East Carolinian. February 1, 1968. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39328

- Nelson, Patti. “Negro Committee Maps Plans To Stop Race Discrimination.” East Carolinian. January 11, 1968. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39322

- Oral History Collection: Charles Davis Oral History, https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/63065

- Owens, Bill. “Discriminations.” East Carolinian. January 9, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39321

- Rabhan, Sandra. “Committee Challenges For Racial Solution.” East Carolinian. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39333

- “Solution Presented.” East Carolinian. January 11, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39322

- “Student Society Plans Relations Improvement.” East Carolinian. March 26, 1968. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39340

- “‘Undesirables.'” East Carolinian. April 2, 1968. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39341

- “USSPA Convention Centers On Black-White Relations.” East Carolinian. December 12, 1967. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39320

Additional Related Material

“Negro Committee Maps Plans to Stop Race Discrimination.” Image Source: East Carolinian, January 11, 1968.

Citation Information

Title: Charles E. Davis

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 2/21/2021