One of East Carolina’s most extraordinary friends in the cause of education in the first half of the 20th century was Charles Montgomery Eppes (1858-1942), supervising principal of Greenville’s African American schools from 1903-1942. A follower of Booker T. Washington’s (1856-1915) accommodationist approach to pedagogy and race relations, Eppes advocated hard work, racial self-help, and public harmony with the white leaders of his day. In the process, Eppes helped coordinate major improvements in African American education in Greenville and much of the state, incrementally deconstructing with relentless civility and kindness, well-directed compliments, and occasional fawning, the worst excesses of the Jim Crow era. By the time of his passing in 1942, Eppes had outlived and out-served, as a teacher-administrator, all his peers, black and white, establishing a state record, unbroken still, of 65 years active service as a public-school educator.

Recognizing Eppes’ achievements, the Carolina Times, an African American newspaper published in Durham, honored Eppes upon the completion of his 65th year in teaching by dedicating much of its May 31, 1941 issue to him. The issue brimmed with public tributes including one by ECTC president, Dr. Leon R. Meadows (1884-1953). Meadows expressed his delight that the May 31 issue honored “Professor C. M. Eppes of Greenville,” adding “I have known Professor Eppes for more than a quarter of a century and have found him to be outstanding among his race, and also a leader of marked ability. You probably could not choose one of his race more deserving of his honor.”

Junius H. Rose (1892-1972), superintendent of the Greenville City Schools and longtime faculty at ECTC, noted his pleasure to have Eppes “as supervising principal of the Negro schools in Greenville.” Rose added that due to “the faith of the School Board and the citizenship in Professor C. M. Eppes,” when Greenville began a school construction program in 1924, “the first building built was the Fleming Street School,” a “modern school … for Negroes.” With admiration, Rose stated that “Professor Eppes has always fought for the rights of Negroes, but he has fought in such a fine manner that he has not made enemies among the white race in so doing, and today numbers of the things which he fought for years ago, are now being incorporated into the State school program for Negroes.”

Greenville’s mayor, B. B. Sugg (1884-1975), declared Eppes “one of the most valuable living citizens in our City and State, … truly a statesman” who “ranks along with Booker T. Washington … in demonstrating that progress can always be achieved.” The City of Greenville sponsored a full-page tribute to “Prof. C. M. Eppes … congratulating him upon his 38 years of faithful service to our beloved City of Greenville.” Greenville businesses including the E.B. Ficklen Tobacco Company, Greenville Tobacco Company, John Flanagan Buggy Company, Blount-Harvey, Coca-Cola Bottling Co., Royal Crown Company, Person-Garrett Tobacco Company, the Plaza Theatre, Guaranty Bank, Belk-Tyler’s, Garris-Evans Lumber, and others published statements of commendation praising Eppes’ efforts on behalf of the educational system and “inter-racial understanding in the City of Greenville.”

Even before ECTTS opened, Eppes was well known to its founding fathers. In July of 1902, W. H. Ragsdale (1855-1914), then superintendent of Pitt County Schools, worked with Eppes, then superintendent of the Plymouth Normal School for Colored Teachers, in convening the Pitt County Institute for Colored Teachers in Greenville. Eppes spoke at the institute on the importance of training students to be polite and to understand “the nobility of labor.” Two Greenville attorneys, Isaac A. Sugg (1848-1908) and Fordyce C. Harding (1869-1956), made addresses “outlining the position of the white people with respect to negro education.” Harding later served as a member of the ECTTS board of trustees, and then in his capacity as state senator, introduced legislation upgrading ECTTS to ECTC. Eppes’ relations with Ragsdale were apparently close: Eppes marched with Ragsdale’s funeral procession to Cherry Hill Cemetery. Indicative of his standing in the white community and his ability to renegotiate segregation, Eppes on occasion offered to arrange for his teachers and students to sing hymns such as “Lead Kindly Light” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” at the funeral services of prominent white friends of the African American community.

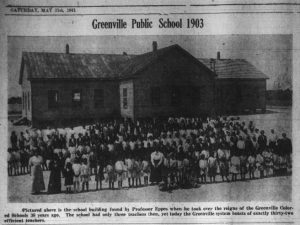

In 1903, following the closing of the Plymouth Normal School, former Gov. Thomas J. Jarvis (1836-1915), then chairman of the City School Board, recruited Eppes to serve as a teacher and principal for Greenville’s “colored school.” The latter then consisted of a three-room wooden structure housing three teachers and 167 students. Nevertheless, by the end of his first year, the state press praised Eppes for coordinating a gathering at the school which was, “for the first time in the history of the town” attended by “a large number of white citizens.” At the event, Fordyce Harding delivered an address, one “highly appreciated by the colored people.” Again, without daring to challenge Jim Crow, Eppes found ways to bring people together, softening the lines of segregation with educated civility. Impressed with Eppes, Jarvis arranged for him, in 1910, to attend a speech by Booker T. Washington in Washington, N.C., and even provided Eppes with a signed, handwritten letter of introduction, to be delivered to Washington personally. In return, Washington wrote back to Jarvis thanking him and noting how he appreciated meeting the local educator. Thus, through Jarvis, Eppes came to the attention of the nation’s leading African American intellectual in the early 20th century.

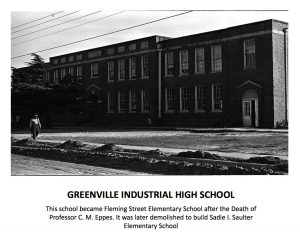

In 1924, Eppes’ leadership bore fruit with the construction of a stately two-story brick facility equipped with running water, heating, electricity, and the latest accoutrements. The new school, the Greenville Industrial School, also known as the Fleming Street School, had 32 teachers and hundreds of African American students ranging from elementary through high school. It was there that Eppes served as principal for the remainder of his life. Built on the grounds of the old clapboard structure which fell victim to fire in 1923, the Industrial School served as a center of African American education in Greenville for the next forty years before being replaced in 1967 by a new elementary school built on the same site. The latter was later named after its first principal, Sadie Irene Saulter (1890-1969), a High Point educator hired with Eppes’ backing.

Eppes wrote numerous letters to prominent papers praising the educational work of white political leaders such as former Govs. Thomas J. Jarvis and Charles B. Aycock (1859-1912). Eppes had good reason to admire Aycock: the latter, while superintendent of Wayne County Schools, gave Eppes his first job teaching. Eppes was active at the state level, serving as a charter member of the North Carolina Negro Teachers’ Association. He also served as executive secretary of the North Carolina Negro High School Athletic Association and chaired the Advancement Council for Negro Scouts of the East Carolina Council. Successive governors including Locke Craig (1860-1924), O. Max Gardner (1882-1947), and Clyde R. Hoey (1877-1954), appointed Eppes to councils and commissions including most notably the Inter-Racial Commission of North Carolina. Dedicated to advancing African American education at all levels, Eppes called for ample funding for the North Carolina College for Negroes, the first state-supported four-year liberal arts college for African Americans in the nation (today, N. C. Central University).

By the spring of 1936, Eppes’ promotion of African American education and friendly race relations facilitated a visit by Fleming Street School students to an ECTC Science Fair “Open House.” One student, Sara Madelyn Taylor, then 13, wrote a prize-winning essay on her experiences that day. The essay appeared in the ECTC newspaper, the Teco Echo. Although brief, the visit – coordinated with Eppes’ blessings – crossed lines, breaching them on campus two decades before the 1954 U. S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregation unconstitutional, and then, in the mid-1960s, the eventual desegregation of East Carolina.

In 1941, writing in support of a local school bond, Eppes invoked “the spirits of the late Governor Thomas Jarvis, W. H. Ragsdale, and the late Senator Fleming” as forces that still “hovered over Greenville” and “seemed to enter into the movements of present-day citizens.” Generously, Eppes credited Jarvis (an outspoken white supremacist) with having instilled in Greenville “the leaven of interracial good will.” The same year and just one prior to his passing, a grand new brick school for African Americans, including a sizable gymnasium-auditorium, was constructed on West Fifth Street and named in his honor. At Eppes’ request, it was in the new auditorium that his funeral was held. Indicative of Eppes’ high standing in the community, Mayor Bruce Sugg and School Superintendent J. H. Rose delivered remarks eulogizing his work.

Throughout his life, Eppes worked fully aware that African Americans could fall victims to Jim Crow racial violence, and in one letter published in the News and Observer in 1940, concluded his cautionary remarks by stating: “Remember Wilmington and 1898,” alluding to the murderous overthrow of what had been the state’s most politically empowered African American community. As a vocal accommodationist, Eppes emerged, in the 1930s, as a critic of the NAACP and its aggressive thinking on racial issues. Although later scorned by more forthright advocates of civil rights, Eppes provided his critics solid shoulders on which to stand and gained for them considerable credibility through his achievements in the educational growth of Greenville’s African American community. Without calling for a wholesale undoing of past injustices, Eppes orchestrated pedagogical initiatives that effectively bent the rules, crossed lines, and facilitated, in small but meaningful ways, enlightened mixing rather than blind, brutal exclusion. The wisdom of his labors became evident in the two modern school facilities built during his tenure and the tens of thousands of African American students who attended them. Today, Eppes’ name remains prominent in Greenville on the Middle School named after him on Elm Street, a school earlier named after Eppes’ colleague in Greenville education, J. H. Rose. The Eppes Cultural Center on West Fifth Street, located on the grounds where the C. M. Eppes School once stood, also preserves his memory.

Sources

- “Colored People Are Organized.” Greenville News. January 30, 1918. P. 4.

- “Colored School Students Exhibit Samples of Work.” Greenville News. June 4, 1920. P. 1.

- “Colored Student Writes Essay for Teco Echo.” Teco Echo. May 13, 1936. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/38042#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=3&xywh=1320%2C326%2C1761%2C1808

- “Creation of Discord is Scored by Epps: Negro Leader Says N.C. White Men Are Best of Entire South.” News and Observer. December 23, 1933. P. 3.

- “Dedication.” The Eppesonian. 1955. https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/38751#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=5&r=0&xywh=-657%2C-823%2C6489%2C3943

- Epps, C. M. “Better Provision for Negro School Children.” News and Observer. August 4, 1924.

- Epps, C. M. “Contribution for Monument.” News and Observer. May 12, 1912. P. 19.

- Eppes, C. M. “Dr. Mordecai Johnson.” News and Observer. April 7, 1938. P. 4.

- Eppes, C. M. “Good Will.” News and Observer. January 13, 1940. P. 4.

- Eppes, C. M. “Greenville City Schools.” News and Observer. November 3, 1941. P. 4.

- Eppes, C. M. “Negroes and Schools.” News and Observer. March 16, 1936. P. 4.

- Eppes, C. M. “Letter to Mrs. [George Edward] Harris.” Undated. Personal copy provided by Bill Kittrell.

- Eppes, C. M. “Pleads for College for Negroes.” News and Observer. February 3, 1927. P. 4.

- Eppes, C. M. “Thoughtful Negroes Grief Stricken.” News and Observer. April 7, 1912. P. 1.

- Eppes, C. M. “Vocational Training.” News and Observer. February 4, 1941. P. 4.

- Epps, Charles M. “A Negro’s Tribute.” News and Observer. May 17, 1904. P. 4.

- Eppes, Charles M. “Today’s Issue.” News and Observer. August 3, 1939. P. 4.

- Eppes, Chas. M. “A Colored Man’s Appeal: Let Educational Policy Stand, Care for Youthful Criminals and Go After Vagrants.” Morning Post (Raleigh). January 20, 1905. P. 4.

- Eppes, Chas. M. “Communicated.” Roanoke Beacon (Plymouth). May 2, 1902. P. 4.

- Eppes, Chas. M. “Negro in North Carolina: Boston Attack on Governor Bitterly Resented.” Washington Post. September 1, 1902. P. 4.

- Eppes, Chas. M. “Racial Unrest: A Discussion of Timely Topics by a Negro Educator.” Morning Post (Raleigh). September 1, 1903. P. 4.

- “Expression of Thanks.” Morning Post. March 12, 1905. P. 4.

- “Fine Effort is Made to Give Employment: White and Colored People Unite to Afford Relief in Greenville.” News and Observer. March 15, 1931. P. 8.

- “Funeral Rites Held for Negro Educator.” News and Observer. August 4, 1942. P. 7.

- “Greenville Educator Honored.” Carolina Times. May 31, 1941. P. 1. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1941-05-31/ed-1/seq-1/

- Hill, Steven A. “Eppes, Charles Montgomery.” NCpedia. 2017. https://www.ncpedia.org/eppes-charles-montgomery

- Hill, Steven A. “Rose, Junius Harris.” NCpedia. 2017. https://www.ncpedia.org/rose-junius-harris

- Hill, Steven and Reflector Staff. “Educator followed his own path to raise up his race in Greenville.” Daily Reflector. February 17, 2019. https://www.reflector.com/features/local/educator-followed-his-own-path-to-raise-up-his-race/article_533d7f43-de3b-5687-900a-63b9432ec0c4.html

- “Local Items.” Tarborough Southerner. June 15, 1905. P. 4.

- Meadows, Leon. “Letter to the Editor.” Carolina Times. May 31, 1941. P. 2. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1941-05-31/ed-1/seq-2/

- “Mrs. B. L. Hardison Dead.” Morning Post (Raleigh). June 7, 1904. P. 5.

- “Negro Education: Profs. Bruce and Epps Open a Campaign in the East.” Morning Post. July 29, 1902. P. 3.

- “Negro Educator Dies in Raleigh: Charles M. Eppes, 85, Was Greenville Principal for 39 Years.” News and Observer. August 1, 1942. P. 2.

- “Negro Leader Makes Appeal: C. M. Epps Tells Colored Farmers to Raise Food and Feed.” News and Observer. December 29, 1929. P. 12. https://www.newspapers.com/image/651039936/?terms=C.%20M.%20Epps&match=1

- “Negro Teacher Lauds State School Forces.” News and Observer. April 16, 1938. P. 2.

- “Officials of Schools Guests at Luncheon.” News and Observer. May 22, 1938. P. 3.

- “Officials to Attend Eppes Funeral Today.” News and Observer. August 3, 1942. P. 10.

- “Proclamation: Office of the Mayor of the City of Greenville.” July 2, 2010. https://www.greenvillenc.gov/home/showdocument?id=2384

- Reflector Staff. “C. M. Eppes Middle School.” Daily Reflector. November 18, 2019. https://www.reflector.com/news/local/c-m-eppes-middle-school/article_0bad05d1-95cf-591f-b195-985a0b13ffb9.html

- “Rejoice in Friendly Relations of Races.” News and Observer. October 12, 1927. P. 9.

- Rose, J. H. “Letter to the Editor.” Carolina Times. May 31, 1941. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1941-05-31/ed-1/seq-2/

- “Sane and Practical is Position Taken by the N. C. Colored Teachers.” Winston-Salem Journal. June 17, 1919. P. 7.

- “School Dedicated in Negro’s Name.” News and Observer. January 29, 1940. P. 5.

- “School Board Guest of Colored Schools.” News and Observer. May 21, 1922. P. 9.

- “Sen. Harding Speaks to Colored People.” News and Observer. February 25, 1918. P. 1.

- “Should Be Commended.” Greenville News. January 31, 1918. P. 2.

- Sugg, B. B. “Valuable Citizen.” Carolina Times. May 31, 1941. P. 1. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1941-05-31/ed-1/seq-1/

- “Teachers Institute.” King’s Weekly. July 15, 1902. P. 2.

- “Thirteen Teachers Have 50-Year Record: Charles M. Eppes, Negro, Holds Record for Length of Teaching Service.” News and Observer. September 17, 1938. P. 7.

- “Urging Race Harmony Between Races: C. M. Eppes Gets Out Letter to His People.” News and Observer. September 26, 1919. P. 24.

- Whitfield, James. “Greenville Negro Boasts 65 Years as an Educator: 83-Year-Old Principal and Alumnus of Shaw Remains Active in Profession.” News and Observer. June 3, 1941. P. 13.

- “Why West Greenville?” https://www.greenvillenc.gov/Home/ShowDocument?id=6464

- Yenser, Thomas, compiler. “Eppes, Charles Montgomery.” Who’s Who in Colored America: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living Persons of African Descent in America, 1933-1937. New York: Thomas Yenser, 1937. P. 175. And, Who’s Who in Colored America, 1938-40. New York: Thomas Yenser, 1940. P. 176. And, Who’s Who in Colored America, 1941-44. New York: Thomas Yenser, 1944. P. 176.

More Images

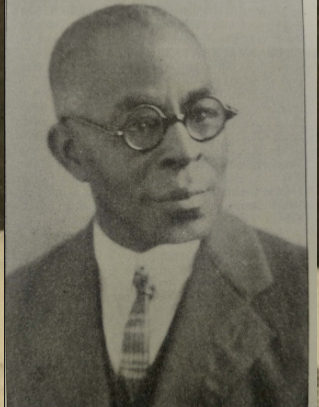

Image Courtesy of the Pearce/Roger Kammerer Private Collection.

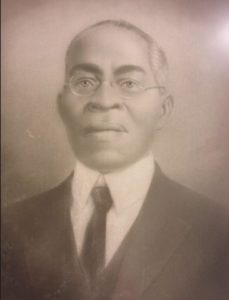

Image of portrait that hangs in the Eppes Cultural Center

Image Source: “Why West Greenville?”

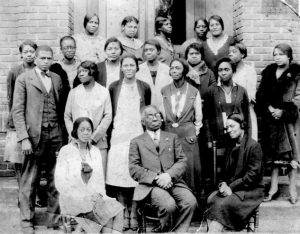

Image Source: The Carolina Times, May 31, 1941.

Citation Information

Title: Charles Montgomery Eppes

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 8/13/2020