William Kerr Scott was born on April 17, 1896 in Haw River, Alamance County, North Carolina. He attended public schools in Hawfields before enrolling at North Carolina State College in Raleigh where he was a member of the track and debate teams. Scott graduated in 1917 with a degree in agriculture before enlisting in the U.S. Army. During World War I he served as a private in a field artillery unit. In 1919, he married Mary Elizabeth White with whom he raised three children: Robert, Osborn, and Mary.

From 1920-1930, Scott managed a farm in Alamance County while also acting as an area farm agent. From 1930-1933, he served as a master of the North Carolina State Grange before accepting the role of regional director of the Farm Debt Adjustment Program, Resettlement Administration. In 1936, Scott embarked on his political career when he was elected North Carolina Agricultural Commissioner. The “Squire of Haw River” as he was known gained statewide acclaim in this role. He successfully organized a campaign to eliminate bovine Bangs disease, an infection which caused miscarriages and premature calving.

In 1938, the Progressive Farmer recognized Scott as their Man of the Year. His followers, popularly known as the “Branchhead Boys,” convinced Scott to resign as Agricultural Commissioner and run for governor in 1948. The Branchhead Boys was comprised of poor, rural citizens with whom Scott’s vow to “get the farmer out of the mud so famers could get to church and farm children to school” resonated.

Campaign manager, Capus Waynick, along with the Branchhead Boys successfully stumped for Scott and propelled him to the governor’s mansion with nearly 74% of certified votes. As governor, he introduced the “Go Forward” program, an ambitious state infrastructure improvement plan that was initially resisted by the legislature. Scott’s popularity pushed the $200 million bond measure through, an astounding $2 billion when adjusted for modern inflation. The funds provided for major improvements to roads and schools. In the first year of the Go Forward program nearly 83,000 telephones were installed, 4,658 miles of road were paved, and electricity reached 88% of North Carolina’s rural population. Improvements were also made to the ports of Morehead City and Wilmington.

A progressive, Scott appointed Harold Trigg to the State Board of Education, its first African American. He also appointed the first female superior court judge, Susie Sharp. Scott’s initiatives also eliminated pay inequality by race at the state mental hospital, introduced stream pollution control, and a motor vehicle inspection program. He was also a supporter of the North Carolina Museum of Art.

In 1954, Scott was elected to the United States Senate where he served until his death on April 16, 1958. However, Scott's “progressivism” never went far beyond the system of racial segregation sanctioned by the Plessy vs. Ferguson Supreme Court Decision of 1896, the year of his birth. As a U. S. senator, Scott signed the 1956 “Southern Manifesto” pointedly opposing the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) decision declaring “separate but equal” facilities unconstitutional. The manifesto said the decision was a “clear abuse of judicial power.”

When Brown vs. Board of Education was announced, Kerr Scott declared, “I have always opposed and still am opposed to Negro and white children going to school together.”1 He also remarked, “It is my belief that most white and Negro citizens of North Carolina agree on this point. I feel certain that no candidate would favor the end of segregation, and I am sure they will join me in hope and prayer that we can avoid stirring up fear and bad feeling between races in North Carolina.”2

As a U.S. Senator, Scott called the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first since Reconstruction, “shrewdly contrived, vicious.” However, Scott supported the “emasculated” version that eventually passed.

Scott died the following year at age 61.

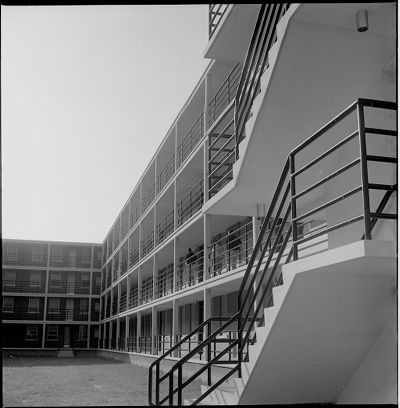

He is buried in Hawfields Presbyterian Church Cemetery near Mebane. The W. Kerr Scott Dam and Reservoir in Wilkes County and Scott Residence Hall on the campus of East Carolina were both named in his honor. His son, Robert, was elected Governor of North Carolina in 1968.

Sources

- 1 This is one of the most frequently quoted remarks Kerr Scott made on race relations. It appears in Rob Christensen, The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics: The Personalities, Elections, and Events that Shaped Modern North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), p. 150. John Drescher, Triumph of Good Will: How Terry Sanford Beat a Champion of Segregation and Reshaped the South (University Press of Mississippi, 2000), p. 16. Julian M. Pleasants, The Political Career of W. Kerr Scott: The Squire from Haw River (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

- 2 Ted Ownby, ed., The Role of Ideas in the Civil Rights South (University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 99.

Additional Related Material

Citation Information

Title: William Kerr Scott

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/1/2019