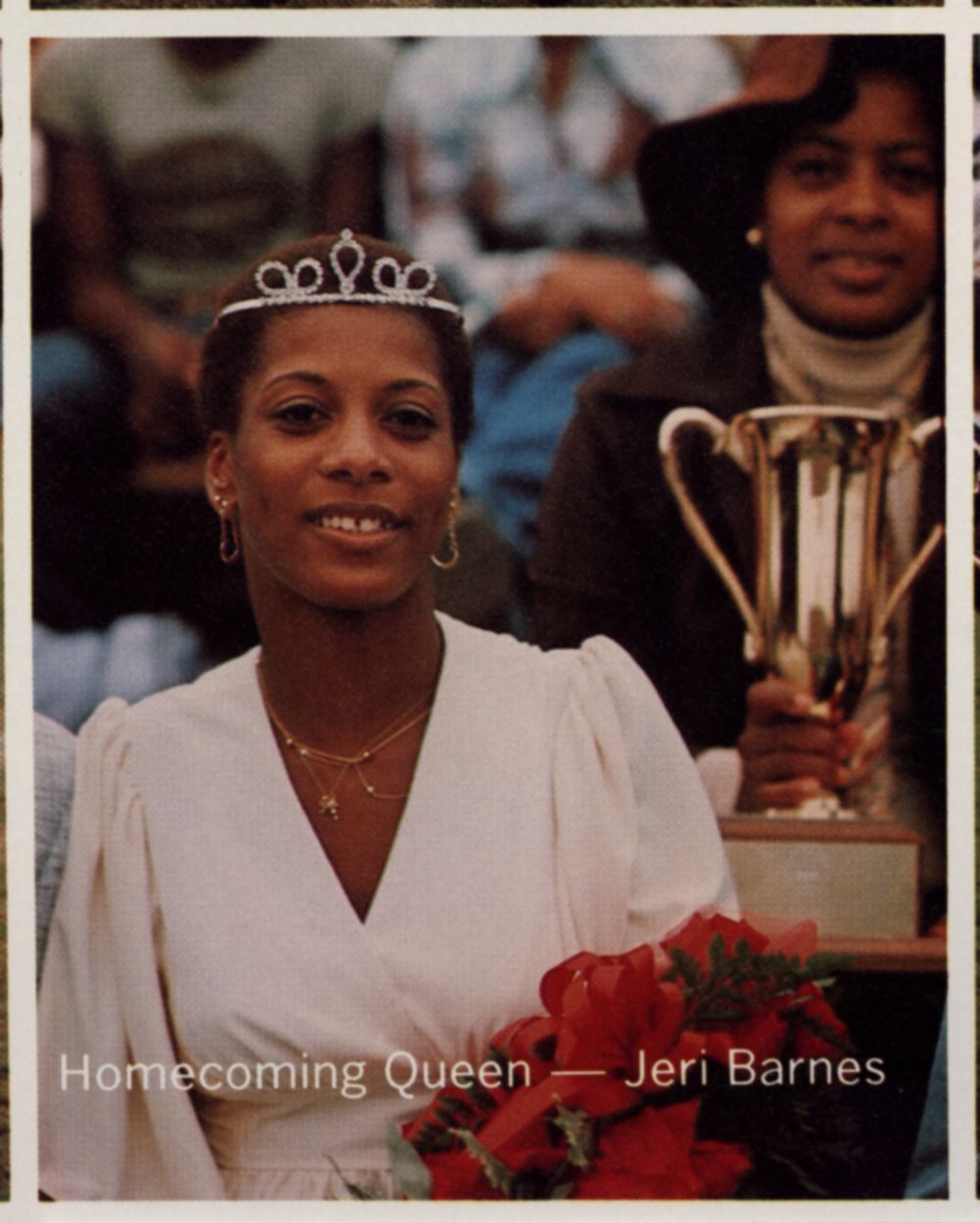

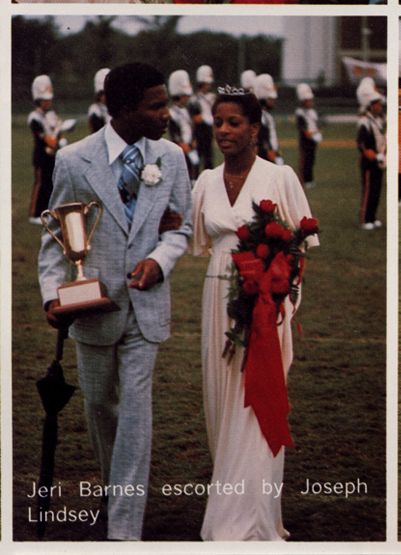

Prior to 1975, ECU homecomings featured a homecoming queen elected by the student body, and a Miss Black ECU, selected by SOULS (the Society of United Liberal Students). Both winners were crowned at halftime during the homecoming game played in Ficklen Stadium. In 1975, the Homecoming Steering Committee decided to do otherwise: it proposed that SOULS enter a candidate for the whole school competition and discontinue the Miss Black ECU contest. SOULS agreed and entered Jeri Barnes, a sophomore from Goldsboro. Ms. Barnes captured the title and became the first black ECU Homecoming Queen.

Ebony Herald covered the historic moment with appropriate detail. In addition to a front-page picture of Ms. Barnes, labeled “ECU Homecoming Queen,” it ran a congratulatory piece several hundred words long recognizing Ms. Barnes as an outstanding sophomore majoring in early childhood education. Along with pride, Barnes offered thoughtful reflections on her achievement. She mused that future black coeds might be challenged to achieve the same honor because there were many who did not want it to happen again.

Indeed, other student media were not as eager as Ebony Herald to recognize the historic moment. The main student newspaper, the Fountainhead (formerly, the East Carolinian), offered first and unfortunately scanty coverage of Barnes’ selection. It published nothing more than a front-page photo of Barnes with tiara and roses, captioned, “During Halftime Ceremonies at Saturday’s football game Jeri Barnes was crowned Homecoming queen.” There was no write-up about Ms. Barnes, nor mention of the historic nature of her crowning.

Letters to the editor soon criticized the lack of coverage. Pointedly, one student complained, “A young lady made history and you just barely mention her name.” The student added, “You fail to tell the readers anything about Miss Barnes. Do I detect a sign of discrimination?” Another student protested, “I looked on every page for an article on the Homecoming Queen and didn’t find one. Now I would like to ask, why? … It is truly a disgrace … there it was, history in the making and not even a cover story. The fact that she was the first black to win the title was enough in-itself for an article. I realize that a lot of people may have been shocked that she won, but she won and deserves credit.” The Fountainhead’s neglect of the historic moment thus quickly turned it into racially nuanced controversy. Campus segregation might have been history, but Jim Crow still lurked, now in the form of silence.

In the following issue of the Fountainhead, Barnes’ disappointment at not being invited to sit in the chancellor’s box for the homecoming game – as had previous homecoming queens, was made public. Barnes stated, “I am not just a queen for the blacks. I am the ECU homecoming queen and that’s the way I feel I should be accepted.” She added, “I can understand individual students not accepting me, but not Dr. Jenkins. Maybe he felt I would have been uncomfortable sitting in his box, but I would not have.” Jenkins denied that there were racial issues in the decision. He reportedly explained that following the previous year’s homecoming, it was decided that “the queen would be most comfortable sitting with her family and friends.” The year before, however, both the homecoming queen and Miss Black ECU had been invited to sit in the chancellor’s box. To rectify the matter, Jenkins invited Barnes to join him for the ECU-Furman game on November 1, 1975. Barnes declined.

A year later, in retrospect, Ebony Herald ran another front-page article, “Queen treated unfairly,” claiming that Barnes was “disappointed with the lack of recognition and acceptance she received during her reign.” According to Barnes, the student body did not accept her. “I was only accepted by the people who voted for me. There was no effort by the school to allow me to represent them.” Barnes claimed that “Dr. Jenkins apologized to me, and made an effort to accommodate me. He asked me to sit in his box at a later game, but I didn’t accept that.” According to Barnes, the Homecoming Steering Committee had earlier emphasized to the contestants that the winner would be asked to sit in the chancellor’s box. Once her selection was announced, Barnes said “Dr. Jenkins showed a negative attitude (during the ceremonies). He didn’t smile, and pictures will show it. He seemed disgusted.” Also noted was that following her crowning, there were “boos from the crowd.” Barnes said she heard them, but “was too happy and they didn’t affect me.” Moreover, Barnes noted that she was not allowed to ride in the Greenville (Christmas parade) and she received poor coverage in both the Buccaneer and the Fountainhead. In Barnes words, “Personally, I feel my treatment was unjust and unfair. I think the whites said, ‘well they (blacks) got it, but so what, we are not going to let them do anything.’”

Well-aware of the historic moment and controversy that followed, the Buccaneer devoted attention to the 1975 homecoming queen selection with a curious headline, “Miss Black ECU Eliminated, Black Candidate Wins Crown.” The Buccaneer followed with a full-page, nine-photo grid, with eight featuring white coeds and escorts walking onto the field. In the center, wearing the tiara and holding roses was Jeri Barnes, homecoming queen, without escort. Standing behind her was another black female holding the gold-plated cup. Buccaneer coverage of previous homecoming queens had been varied, but the 1976 volume afforded, at least in pictorial presentation, one of the most minimalistic celebrations of the homecoming queen ever. No doubt, in campus culture of the 1970s, homecoming celebrations had faded in prominence. Nevertheless, the scanty treatment Barnes received, on campus, in student media, community events, and administrative decisions evidenced a level of insensitivity if not callousness that reflected poorly on the quality of progress made toward a more diverse and inclusive environment recognizing the dignity, integrity, and achievements of all.

Sources

- "An ECU First …" Ebony Herald. November 14, 1975. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/57047.

- Bonnerman, Ronnie. "Lack of story on queen noted." Fountainhead. October 23, 1975.

- Campbell, Kenneth. "Queen treated unfairly." Ebony Herald. Vol. 3, no. 3. October 1976. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/56982.

- DeLoatch, Joseph. "Student cites poor paper coverage." Fountainhead. October 23, 1975.

- Dink. "Poetry Anyone?" Ebony Herald. November 14, 1975. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/57047.

- "During Halftime Ceremonies." Fountainhead. October 21, 1975.

- "Homecoming." Buccaneer. Greenville, N.C.: East Carolina University, 1975. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15326.

- "Homecoming." Buccaneer. Greenville, N.C.: East Carolina University, 1979. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15358.

- "Miss Black ECU Eliminated, Black Candidate Wins Crown." Buccaneer. Greenville, N.C.: East Carolina University, 1976. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15327.

- "On Becoming Queen." Ebony Herald. November 14, 1975. P. 7. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/57047.

- Woodard, Helena. "Homecoming queen disappointed." Fountainhead.

Additional Related Material

Citation Information

Title: The First Black ECU Homecoming Queen, Ms. Jeri Barnes, 1975

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/18/2019