Friends of East Carolina Teachers Training School came in many shapes and sizes. Among the most important were the town of Greenville and the succession of public schools built near the ECTTS campus. These town schools enhanced the standing of the training school and strongly reinforced its progressive educational mission. In the early twentieth century, the most significant of these schools was Greenville High School, founded in 1915, just six years after ECTTS opened. From its construction the following year until it burned in 1968, GHS was well-located to work hand-in-hand with the training school, then later, the teachers college, and finally, the college and university.

Although founded as a high school, the GHS building was repurposed in the mid-1950s as the town’s junior high following construction of a new high school facility, J. H. Rose High, first located on Elm Street next to College Hill. Later, a new elementary school, Elmhurst, was built across Fourteenth Street from Rose and College Hill. Elmhurst soon became next-door neighbor, in the early 1960s, to Ficklen Stadium (later Dowdy-Ficklen) and East Carolina’s new athletic campus. As with GHS, Greenville’s public schools thus reaffirmed, by surrounding the campus with public facilities, support for and active involvement in East Carolina’s role in promoting educational progress. These public schools were, however, like ECTTS, chartered within the confines of the Jim Crow era and so exclusively provided for – until the early 1960s – the education of the town’s white population. Greenville did establish public schools for African Americans but they were in every case substandard and invariably located on the west-side of town, some distance from the training school and its mission of educating young white men and women. While the U.S. Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision sanctioned segregation provided that arrangements were “separate but equal,” Greenville’s provisions for African American education were hardly equal though they were clearly separate.

The intimate relationship between Greenville and ECTTS was evident from early on. Following 1907 legislation founding the school, the North Carolina Board of Education accepted bids from municipalities in eastern North Carolina seeking to become the home for the new school. Flush with wealth generated by the newest cash crop, tobacco, Greenville won the competition with its $100,000.00 pledge plus a campus site of nearly 50 acres. The $100.000 pledge was based on a $50,000 pledge by the town and an additional $50,000.00 by Pitt County. While Kinston offered a more sizable 200-acre campus, Greenville’s $100,000 bid topped all others, securing for it the new teacher training facility. As led by former governor Thomas J. Jarvis, chair of the Building Committee, the $100,000 was spent on building the original campus. State money was forthcoming for upkeep, salaries, and future expansion, but in effect Greenville and Pitt County built the new “state” school.

Four years earlier, Greenville had modernized its public school system with construction of a new educational facility on the grounds once occupied by the clapboard Greenville Academy, a private school run by William H. Ragsdale, later a professor of pedagogy at ECTTS. The new two-story brick school, known as Evans Street Graded School, opened in 1903 offering instruction from elementary grades through high school. The chairman of the school board at that time, former Gov. Jarvis, later played a crucial role in securing legislation for the founding of ECTTS, its location in Greenville, and in overseeing its construction. Jarvis’ earlier support for the Evans Street School foreshadowed his subsequent work on behalf of ECTTS and the educational revolution that soon unfolded in Greenville. While progressive in many ways, the transformation of Greenville from a tobacco boomtown into an educational hub populating the entire state with professionally trained teachers was unfortunately limited by the “separate but equal” Jim Crow system of segregation then prevalent.

The impressive, two-story brick Evans Street School was within easy walking distance of the campus, but seemed even closer after Greenville financed, in 1914, another educational facility, the “Model School,” located on the west end of ECTTS facing Cotanche Street, just a block from Evans Street. The Model School served as a practice facility for ECTTS teachers in training and was administered jointly by ECTTS and the Greenville School Board. For all practical purposes it was an addition both to the Greenville public school system, expanding its facilities for elementary education, and to the ECTTS campus and its teacher training curriculum. With the Model School, an educational symbiosis emerged wherein the pedagogical bounds of Greenville and ECTTS often overlapped and at times seemed indistinguishable.

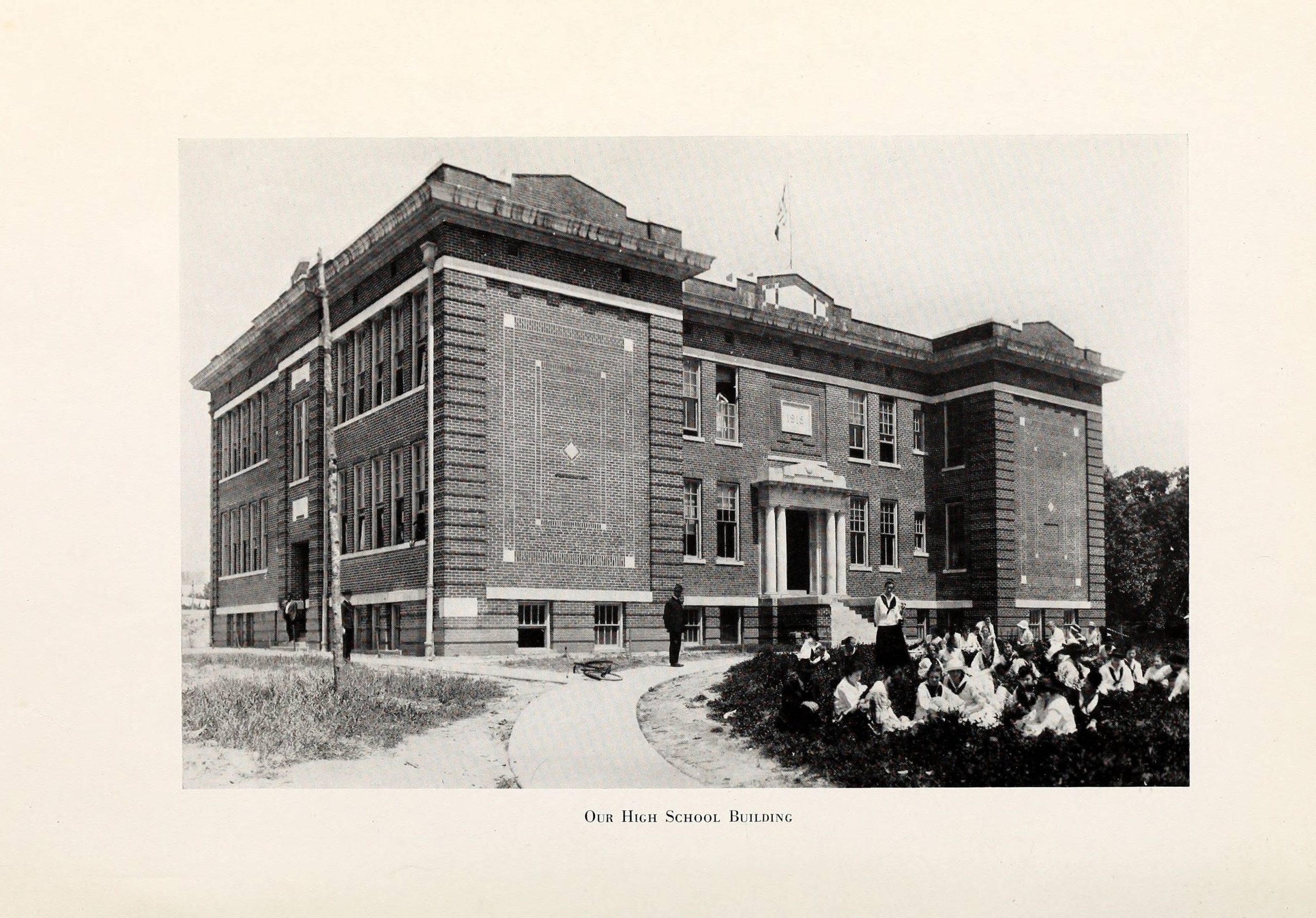

The following year, 1915, Greenville embarked on a further expansion, soliciting bids for construction of the town’s first dedicated public high school, GHS. The building site, on the corner of Reade and Fifth, was cattycorner to ECTTS and might have appeared, to the naïve observer, as another impressive and handsome addition to the campus. With the two-story brick facility, completed in 1916, the town effectively surrounded the western end of ECTTS with a ring of “modern” public schools, ones well removed from the one-room structures of the past, reaffirming thereby solid civic support for the work of the training school.

Emblematic of GHS’s ties to ECTTS and its progressive educational mission, two marble memorial tablets, one honoring Jarvis and the other, former Gov. Charles B. Aycock, were donated by Greenville students to the new high school for display in its auditorium. These memorials to the two leaders, recognized in their day as “education governors” but later criticized for their white supremacist political agendas, tied GHS to ECTTS in both the best and worst dimensions of early twentieth century progressivism linked as it was, especially in the South, to educational advances within the confines of Jim Crow segregation.

As a public facility dedicated to high school instruction, GHS helped prompt ECTTS’s move to the next level of its curricular development, that of a four-year teachers college, enabling it to shed its earlier mission of providing high school course work as well as teacher certification. In 1907, ECTTS had been founded as part of a legislative compromise brokered between James Yadkin Joyner, the state superintendent of education who wanted state funding for public high schools, and those in eastern North Carolina, including Jarvis, Ragsdale, state senator James L. Fleming and others who wanted a training school for teachers for elementary schools. The compromise, embedded in “the general act of 1907 providing for the establishment of public high schools,” chartered ECTTS as a school with a two-tier curriculum: one, a two-year program for students who had not completed a high school degree. The other tier was a two-year program for high school graduates who wanted to earn a teacher’s certificate. ECTTS did not, however, have a four-year program awarding a bachelor’s degree. Instead, it simply offered high school level instruction for those who had none, and a teacher certification curriculum for those who did.

ECTTS President Robert Wright apparently foresaw, from the start, that with the school’s success in training public school teachers and the increased growth in publicly supported high schools statewide, ECTTS would eventually shed its high school curriculum while expanding its teacher certification track into a four-year program awarding bachelor’s degrees and the highest level of NC teacher certification. That materialized in the early 1920s as a push for better education resulted in more high schools being founded and numerous teacher training schools being elevated to teachers colleges, and teachers colleges being upgraded to four-year liberal arts colleges.

Before Greenville, other eastern North Carolina towns such as Washington, New Bern, and Kinston had established their own public high school facilities, each housed in an impressive brick structure. Once Greenville followed suit, the obsolescence of ECTTS’s high school tier became even more evident, as did the real need for teachers with the highest level of certification from a four-year institution. Early on, GHS faculty were exclusively from such schools making it clear that if ECTTS hoped to provide teachers for schools such as GHS, it would have to upgrade its curriculum, as indeed occurred in the early 1920s. Following that move, some new faculty hired at GHS were ECTC graduates, and increasingly GHS graduates thought in terms of applying to ECTC once the four-year bachelor’s degree was an option. In that respect, the pedagogical dynamic between ECTTS and GHS challenged both centers of learning to achieve new heights.

Sources

- “Annual Playground Exercises.” The Tau. 1919. P. 58. https://archive.org/details/tauserial1918gree/page/58/mode/2up

- “Exhibit Tablets at High School.” Wilmington Dispatch. November 5, 1916. P. 5.

- “Greenville and the Training School.” News and Observer. May 25, 1911. P. 4.

- “Greenville Schools Valued Asset.” Greenville News. April 29, 1921. P. 13.

- “High Schools in North Carolina.” Greensboro Daily News. May 15, 1908. P. 6.

- “No Decision Until July 10.” News and Observer. June 28, 1907. P. 3.

- “Proposals, High School Buildings – Greenville, North Carolina.” News and Observer. September 13, 1915. P. 5.

- “The Evans Street School.” The Tau. 1919. P. 57. https://archive.org/details/tau19201920gree/page/n59/mode/2up

- “The Model School.” The Tau. 1919. P. 57. https://archive.org/details/tau19201920gree/page/n57/mode/2up

- “The Third Anniversary at Teachers Training School.” Charlotte Observer. July 1, 1911. P. 7.

Citation Information

Title: The Greenville High School

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/29/2020