A global health crisis – the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic – surfaced in early 2020 prompting nationwide requests that Americans stay at home to slow the viral spread. In mid-March, ECU extended its spring break by one week as students and faculty prepared to shift to online education for the rest of the semester. In line with UNC System policy, interim chancellor Ron Mitchelson told ECU students not to return to campus. Eventually, dorms were closed, as were most campus facilities, though many services continued electronically. Social distancing became the order of the day resulting in cancellation of spring graduation ceremonies as well as myriad end of the year face-to-face meetings. Many declared the university’s aggressive response to the virus attack truly historic and unprecedented.

While certainly historic, East Carolina’s response was not unprecedented. In the spring of 1918, a deadly, global pandemic (H1N1 virus), commonly known as the “Spanish Flu,” emerged, resulting in similar measures, challenging the student body, faculty, staff, and administration in ways that tested the resilience and resolve of the nine-year old teacher training school. Before the 1918 pandemic ended, an estimated 500 million people worldwide had been infected, resulting in 50 million deaths globally and 675,000 in the United States.

In Greenville, the pandemic peaked in the fall of 1918. Aware of the larger health consequences of social gatherings and the chances of spreading sickness through social proximity, churches suspended their services and tobacco warehouses postponed opening day sales. Superior Court Judge Harry Whedbee announced that judicial cases and jury duty were postponed indefinitely. An emergency hospital opened in the Pitt County Courthouse as civic leaders began recognizing what Dr. Charles O’Hagan Laughinghouse, ECTTC’s first campus physician, had called for years before: the need for a public hospital. Between October and November 1918, area physicians reported 5,680 cases of influenza in Pitt County. A Greenville News cartoon warned readers, “Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases, As Dangerous as Poison Gas Shells.” Only the momentous events ending WWI overshadowed news coverage of the deadly epidemic.

However, by the spring of 1919, on ECTTS’s tenth anniversary, Dr. C. O. Laughinghouse could comment, “with the exception of influenza during the fall of 1918, the school has been entirely free of epidemics.” He added, “It is with a great deal of pride that I am able to record the well-nigh miraculous fact that as of this writing we have not had within the school a single death among the student body or the faculty.” Earlier, Laughinghouse had emphasized the importance of up-to-date student heath practices, including vaccines for known diseases. While the Influenza epidemic, 1918-1919. took the world by surprise, Laughinghouse’s well-established concern for campus health provided a solid, progressive foundation for later ad hoc responses by the ECTTS administration.

Still, the pandemic did bring tragedy to the Training School. Just four months after graduating in June of 1918, Sallie Jenkins Tyler fell victim to the influenza. “This [was] the first time the members of a class … had to face the loss of a classmate so soon after they had been in close daily comradeship.” Tyler had taken a position teaching in Roxobel, Bertie County (her home), when she became ill with influenza, “partially recovered, but … [then] overtaxed her strength trying to wait on others who were sick, was taken with pneumonia, and died.” She was buried in her graduation dress. The Training School Quarterly conveyed this sad news, noting that Tyler, a “happy-natured, big-hearted girl, ready to enter into anything that was good and wholesome,” had “truly … [given] her life for others.”

Unlike ECU in 2020 which encountered Covid-19 during spring break, ECTTS confronted the epidemic outbreak at the beginning of the fall semester, the very first week of school. Soon, five girls had reportedly “picked up the ‘flu’ from somewhere.” Writing facetiously, well after the fact, one student account related how the “flu” had become “a very fashionable disease [and that] the rest of us were so anxious to get in the fashion and so sympathetic that about one hundred and forty more fell victims.” Faculty members reportedly served as “nurses during the epidemic.” Seniors scheduled to teach at the Model School were disappointed at having lost the chance to practice what they had learned. Without cancelling classes, President Robert H. Wright assured the student body that if they remained and did their best through exams, they would pass their courses with suitable grades. With just over half of the student body of 278 sick with the flu, to one degree or another, everyone on campus was affected by the Influenza epidemic, 1918-1919.outbreak.

After the Christmas holidays, six faculty “fell victims to the influenza” Four of the six were Model School teachers, prompting Lois Hester, a senior, to comment, “you can imagine what a happy time we poor greenhorn teachers had with those children at the Model School.” Even the ECTTS physician, Dr. Nobles, did not escape the spread. Despite the dire circumstances, things on campus remained under control. Reportedly, “although at times the classes were very small … there was no panic and little distress. The girls, on hearing of the situation at other places, were glad they were at the training school because [the epidemic] was handled so skillfully.” Parents likewise “expressed their appreciation … saying they were glad their daughters were in school because at home the situation was terrible. Everyone was sick and [had] no one to wait upon them, and no chance to hire anyone.”

One student, Mildred Frye, later related how she had changed rooms repeatedly due to the epidemic. With the infirmary “filled to overflowing,” forcing new patients to lodge in the east wing of the west dormitory (later, Wilson Dorm), Frye surrendered her well-situated room, room 2, next to a bathroom, and eventually ended up in the dorm’s last room, room 99. During the six-week on-campus “quarantine,” ECTTS students, not allowed to leave the campus, were provided Sunday School services in the campus chapel, followed by lessons given by faculty in classrooms according to the different denominations of the student body. Bonnie Howard, president of the Y.W.C.A., coordinated these services. Healthy Y.W.C.A. members assisted in serving meals, carrying water, washing dishes, etc., finding in the crisis an opportunity for service. As early as November 15, 1918, President Wright expressed, in remarks to the ECTTS Board of Trustees, praise for the school in coping successfully with the epidemic.

With the 1919-1920 academic year, ECTTS continued, by student vote, a voluntary “conditional” quarantine disallowing contact with off-campus communities suffering from influenza outbreaks. Students were permitted weekend visits home, but they agreed that if there was flu in their community, they would not be allowed to re-enter school until the campus physician gave them permission. When the quarantine was finally lifted in the spring of 1920, the streets were reportedly “filled with happy, bright-faced students, happy to be free once more.” One student, reflecting on the experience, observed that “not a single case of influenza has been in the school this year. This shows how wise it has been to keep strict quarantine.” The solid foundations in leadership and service laid since the training school’s opening nine years prior thus well stood the test of the times in responding, locally, to the lethal challenges of the 1918 pandemic.

Sources

- “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus).” CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

- “After the Quarantine.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 7, no. 3. (April, May, June 1920), p. 279. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu73east/page/278/mode/2up

- East Carolina Teachers Training School Board of Trustees Minutes (November 15, 1918). http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/2881

- Frye, Mildred. “Being Chased by the ‘Flu.’” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 6, no. 1. (April, May, June 1919), pp. 128-129. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu63east/page/128/mode/1up

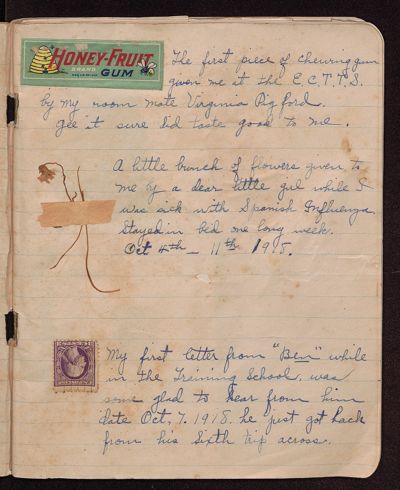

- Grant, Mabel. Diary. Mabel Grant Papers. University Archives. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N.C. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/60884

- Hester, Lois. “A Jumble of Odds and Ends.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 6, no. 1. (April, May, June 1919), pp. 129-130. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu63east/page/129/mode/1up

- Howard, Bonnie. “YWCA.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 6, no. 1. (April, May, June 1919), pp. 74-77. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu63east/page/74/mode/2up

- “Influenza After Christmas.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 5, no. 4. (January, February, March 1919), p. 362. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu54east/page/362/mode/2up

- Laughinghouse, Charles O’Hagan, M.D. “The Health Record.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 7, no. 1 (October, November, December 1919), pp. 24-25. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu71east/page/24/mode/2up

- “Sallie Jenkins Tyler.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 5, no. 3 (October, November, December 1918), p. 279. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu53east/page/278/mode/2up/search/Sallie

- Stokes, Anna Gray. “Breaking Into Teaching at the Model School Without a Model.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 6, no. 1. (April, May, June 1919), pp. 119-120. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu63east/page/118/mode/2up

- “Sunday School During Quarantine.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 5, no. 3. (October, November, December 1918), p. 294. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu53east/page/294/mode/2up

- “The Epidemic.” Training School Quarterly. Vol. 5, no. 3. (October, November, December 1918), pp. 293-294. https://archive.org/details/trainingschoolqu53east/page/292/mode/2up

- “The Spanish Influenza is Here": Memories of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Eastern North Carolina.” Special Collections. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. https://library.ecu.edu/specialcollections/2019/02/11/the-spanish-influenza-is-here-exhibition/

More from Digital Collections

Mabel Grant's diary written during her time as a student at East Carolina Teacher's Training School. This page included some dried flowers that Grant recieved when she was sick with the 'Spanish Influenza."

Postcard showing the Infirmary at East Carolina Teachers Training School, Greenville, N.C. Later used for home economics department and renamed in honor of Mamie E. Jenkins. The building now serves as the home of the ECU Honors College.

Citation Information

Title: The Influenza Epidemic, 1918-1919

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 4/6/2020