Pirates are deeply rooted in North Carolina history and legend. They figured prominently in the state’s colonial past, especially in coastal areas providing ample hiding from official eyes. Most famously, Edward Teach, known in legend as Blackbeard, lived in Bath and then Beaufort before meeting his end near Ocracoke in 1718. Two centuries later, he still captivated the historical imagination of eastern North Carolinians. Maybelle Beacham’s “A Brief History of Beaufort County,” published in the 1920 Training School Quarterly, noted how Blackbeard had married his thirteenth wife in Bath, adding that “an old cannon once in active service for his piratical cruelties” lay buried there near a stone pier. In 1934, the Daily Tar Heel at UNC-Chapel Hill announced an exhibit on pirates at the university’s library replete with manuscripts and books “on the life of Edward Teach … commonly called Blackbeard.” The same year, with astute punning guidance from a history professor, A. D. Frank, East Carolina embraced Blackbeard lore, thus beginning its transformation in athletic and campus identity from “Teachers” to “Pirates.”

When first organized in 1932, men’s athletic teams were known as the “Teachers.” For whatever reason, they did not generate much school spirit. In 1934, the student newspaper, the Teco Echo, solicited new names for women’s sports, indicating openness to a more rousing moniker for men’s sports as well. On February 19, 1934, the paper reported that the Men’s Athletic Association had voted to name its teams “the pirates,” hoping that the new name would inspire “more spirit and enthusiasm.”

The 1934 Tecoan clarified the origins of this change. The yearbook brimmed with colorful illustrations of swashbuckling pirates clad in purple and gold colors, advancing a daring and yet playful vision of school identity. Following the foreword and its account of “the Pirate Teachy and his crew,” i.e., Blackbeard, the 1934 Tecoan announced that it was dedicated to Dr. A. D. Frank for his “thorough instruction in history.” Frank’s enthusiasm for campus athletics and his eye for an adventurous pun – teachers becoming pirates like the pirate Teachy – presumably informed the new identity and its many illustrations. The Teco Echo eagerly endorsed the change, headlining men’s teams and their players as “the Pirates.” Women’s teams, however, came to be called “the Ramblers.” Despite the popularity of “the Pirate,” the old “Teacher” identity died hard, remaining on uniforms, varsity monograms, and sports reporting as an alternative designation into the 1950s.

Nevertheless, from 1934 forward, pirate imagery increasingly dominated campus culture. The first student literary magazine was, in 1939, initially named Pieces O’ Eight. In 1953, the campus yearbook, formerly known as the Tecoan, was renamed Buccaneer. Even before the name change, the Tecoan had featured, in 1951 and again 1952, pirate visages embossed on its covers. Pieces O’ Eight was eventually replaced by Rebel in 1958, but the name Pieces of Eight was revived in 1978 for the faculty and staff newsletter. Also, the newly organized Pirate Club proved to be enormously successful at raising funds for athletic and educational causes. On tee-shirts, caps, businesses, and virtually anything marketable, Pirate motifs have become omnipresent in Pitt County and much of the eastern region, reflecting the charismatic appeal of the motif and giving rise to widespread consciousness of a new cultural region, the Pirate Nation.

As pirate imagery boomed during the 1960s, it provided East Carolina with a dominant means of navigating its transition from Jim Crow to a more diverse and inclusive campus culture. Competing with revivals of “Old South” imagery as symbolized by the Confederate flag and “Dixie,” the Pirate “skull and crossbones” flag, along with tunes such as Jimi Hendrix’s rousing “Purple Haze,” helped lead to a more broadminded identity valuing bold, daring success rather than narrow-minded bigotry. After all, in the Pirate lexicon, the white flag supreme meant the unacceptable, surrender.

Sources

- Buccaneer. Greenville, NC: East Carolina College, 1953. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15304.

- Carlson, Arthur, Elizabeth Brooke Tolar, and John Allen Tucker. East Carolina University Football. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2016.

- East Carolina Football Collection. UA40-01. University Archives, Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

- “Exhibition Shows Manuscripts and Books on Pirates.” Daily Tar Heel. January 5, 1934. P. 1.

- “Pee Dee: A Rational Argument for Removal.” The East Carolinian. September 18, 1984. P. 4.

- Pieces O' Eight. UA50.07. University Archives, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

- “Pirates Accepted as Official Name for Teachers.” Teco Echo. February 28, 1934. P. 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/38014.

- Pyle, Howard. Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates. New York: Harper Brothers, 1921.

- Records of the Department of Athletics. UA40.00. University Archives, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

- Tecoan. Greenville, NC: East Carolina Teachers College, 1934. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15339.

Additional Related Material

Citation Information

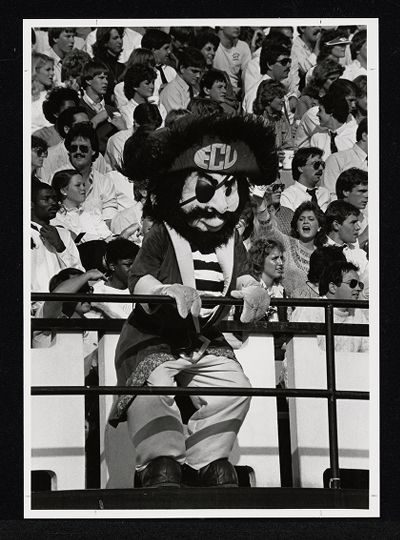

Title: The Pirate Mascot

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/29/2019