With the armistice ending WWI, Germany surrendered its war materials including approximately 5,000 field cannons. Not a few ended up as public artifacts memorializing those lost and commemorating the victory won. One appeared in downtown Asheville at the foot of the Vance Memorial, and another on the campus of East Carolina Teachers College. As interpreted by ECTC president Robert H. Wright, the cannon bore significance as a reminder of the egregious waste of war and the need for greater investment in education. For students, it became a unique, often-photographed fixture that appeared regularly in the campus yearbook, the Tecoan. With WWII, however, the cannon was donated, circuitously, to the national drive for scrap metal. The cannon’s journey was thus from war to peace, and then back.

In 1926, President Wright addressed the student body on the cannon’s significance. Wright began with humor, noting how someone had said “the people of the South do not know how to point a gun any other way except toward the north,” but added that his take on the matter was different. According to Wright, the cannon “is just one of the many, many devices that human beings have made in order that they might kill each other.” He noted that “during the World War it cost $15,000 to kill one man.” Then, along sobering lines, he observed, “That cannon is a memorial of the world’s few years of worship of the God of Destruction.”

Wright’s main point was that far too much was being spent on war, and too little on education. The World War had cost $338 billion, and for two years it had run $10 million per hour, four times the value of “this plant, the college.” Wright added, “Besides the billions of dollars, that gun means the lives of ten million of the selected young men of the world actually killed in battle, and the thirty … [million] wounded and maimed for life, making in all forty million.” Wright stated that North Carolinians paid four dollars for the World War for every dollar they paid in taxes for education. He concluded by stating, “The cannon that we have, I hope from today on, will be a constant reminder to us of what that way of setting international differences is going to cost the world.”

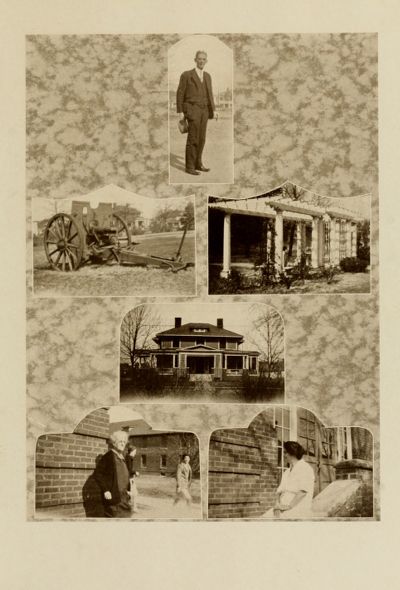

A picture of the cannon appeared the following year in the 1927 Tecoan. There, it stands, alone, pensive and without caption, on an expansive lawn with a bare forest horizon. The very next year, it was featured in the 1928 Tecoan, pointing north toward Fifth Street. Opposite the cannon picture is a separate snapshot of Wilson Pergola. Both are situated beneath a photo of President Wright, and above a picture of the president’s home on Fifth Street. Perhaps Wright’s remarks remained fresh in the minds of students.

However, with the 1929 Tecoan, the cannon became a photo-site for student yearbook pictures. That year, the Washington County Boosters posed around it, virtually covering it from view except for its large wheel. The 1931 Tecoan shows the cannon and campus covered with snow, accompanied by a single student. In another picture from the same yearbook, two students sit atop the cannon during early spring. The 1936 Tecoan showed the cannon in a new location, one positioned next to Wilson Pergola. In this picture, five students are sitting atop the cannon. The 1937 Tecoan includes four women on or next to the cannon, with the playful caption, “No wonder they had a war.” The 1938 Tecoan presents a shot of Bertha Lang, “the cutest,” leaning against its barrel, as well as a snapshot of two students, one standing on her head, with the cannon and pergola behind them. The 1940 Tecoan included three snapshots, two featuring students and the cannon in snow, and the other in spring, with a single student resting her arm on the barrel. Years of peace had transformed the wasteful weapon of war into a unique, apparently beloved campus fixture.

Soon, however, things changed. As involvement in WWII neared, the 1941 Tecoan depicted three students perched on the cannon, with the subtext, “bang, bang.” Following Pearl Harbor, the 1942 Tecoan pictured two students flanking the cannon, fingers in ears, followed by the caption, “Hear no evil.” The 1943 Tecoan presents four students sitting around and atop the cannon, its barrel projecting outwards. However, by the time that yearbook was published, the cannon had departed campus.

The second president of ECTC, Leon R. Meadows, presided over its exit. In the fall of 1942, the Teco Echo reported that “scrap” was “the battle cry of the day, and that “We can help raise a little corner of Hell; maybe in France, maybe in Tokyo, maybe in Berlin, by gathering scrap.” It added that “the old World War I cannon” had been sold to Sam Fleming’s scrap yard.” Because ECTC was a state institution, it could not donate the cannon directly to the scrap drive, but instead sold it for $9.00 so that Fleming could donate it.

Sources

- “President Wright Discusses War and Education.” Teco Echo. December 7, 1926. Vol. 2, no. 5. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/37819.

- Terrell, Bob. “A Walk Through History.” Asheville Citizen-Times. November 11, 1997. P. C2.

- The Tecoan. 1927 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15332) , 1928 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15333) 1929, (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15334) 1931 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15336), 1936 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15341), 1937 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15342), 1938 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15343), 1940 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15345), 1941 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15346), 1942 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15347), 1943 (https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15348). Greenville, N.C: East Carolina Teachers College.

Additional Related Material

Citation Information

Title: The WWI Memorial Cannon

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 7/18/2019