Tracing monumental figures and events

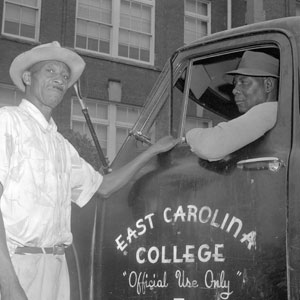

ECCEast Carolina College

In 1951, the state legislature voted to upgrade East Carolina to a four-year college. With an enrollment of over 2000 students, East Carolina had already become the state’s largest public college. In some circles, it was already referred to as the “Eastern University.” Read more…

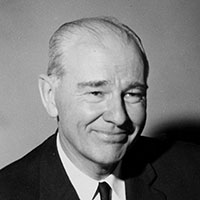

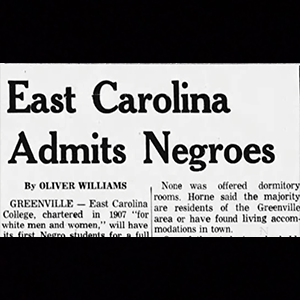

In the 1960s, Jenkins accelerated enrollment growth and oversaw other major transformations of campus culture, academic life, and identity. The student body, 4,000 strong in 1960, had nearly doubled by 1966. This momentum continued throughout the 1960s, making East Carolina the third largest behind UNC and N.C. State. Physical expansion continued, up College Hill with several new dorms, plus a new athletic campus including Ficklen Stadium, Minges Coliseum, a track field, baseball field, and football practice facilities.

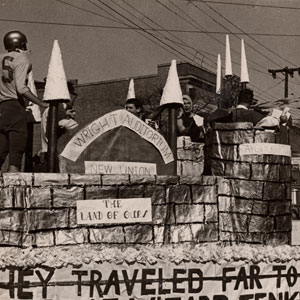

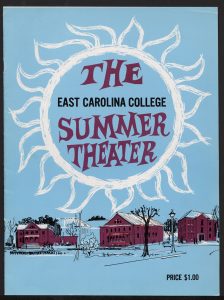

Jenkins brought cultural renaissance to the East by recruiting leaders in art, literature, drama, and music. Academic departments multiplied and new schools were founded. The east end of campus, formerly occupied by College Stadium, was redeveloped with academic buildings housing faculty in art, business, the social sciences, music, and education. Jenkins also cultivated awareness of eastern North Carolina as a region, the East, centered in its “service facility,” East Carolina College.

By the mid-1960s, Jenkins launched a campaign to make East Carolina an independent, regional university. This push ran contrary to the “one-university” strategy accepted by most leaders in state education. Jenkins launched this bold drive with the political support of alumnus, trustee, and state senator, Robert Morgan, and virtually all powerbrokers in the East.

The bid generated statewide controversy. Most commentators understood that if successful, it would entail a major reconfiguration of public higher education. After narrow defeat in March 1967, the school’s sixtieth anniversary, backers warned of political consequences, suggesting the East might go Republican due to its betrayal by other state Democrats.

That summer, Senator John Henley of Fayetteville proposed a compromise: a system of regional universities, with East Carolina first among them. Also included were Western Carolina, Appalachian, and A&T in Greensboro. This bill, opposed by Gov. Dan Moore but supported by Lt. Gov. Robert Scott, passed. With it, not only had East Carolina achieved university status, it initiated a revolution in public university life, catapulting the state’s former teachers colleges to the highest level.

Next: East Carolina University History »